Wearable Ultraviolet Sensors Measure Intensity of Ultraviolet Rays.

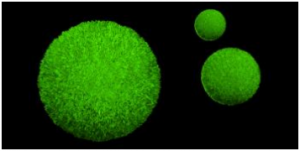

The UV (Ultraviolet is electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength from 10 nm to 400 nm, shorter than that of visible light but longer than X-rays. UV radiation is present in sunlight constituting about 10% of the total light output of the Sun) active ink can be printed on paper making sensors cheap and easy to produce.

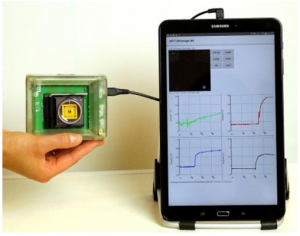

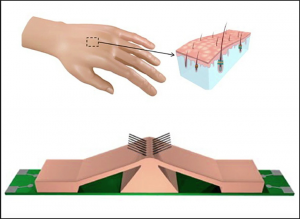

Keeping an eye on your personal UV (Ultraviolet is electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength from 10 nm to 400 nm, shorter than that of visible light but longer than X-rays. UV radiation is present in sunlight constituting about 10% of the total light output of the Sun) exposure throughout the day could soon be as simple as wearing a sticker thanks to new wearable sensors that help people manage vitamin absorption and avoid sun damage.

A personal struggle with Vitamin D deficiency led Professor X to develop the color-changing sensors that come in six variations to reflect the range in human skin tone.

Bansal said the discovery could help to provide people with an accurate and simple measure of their personal exposure levels throughout the day.

“We can print our ink on any paper-like surface to produce cheap wearable sensors in the form of wrist-bands head bands or stickers for example” he says.

While humans do need some sun exposure to maintain healthy levels of Vitamin D excessive exposure can cause sunburn, skin cancer, blindness, skin wrinkling and premature signs of aging.

Knowing what a healthy amount is for you depends on understanding your personal classification, from Type I to VI as each has very different solar exposure needs.

Diseases such as Lupus and many medications increase the photosensitivity of our skin and reduce our ability to absorb Vitamins through diet making monitoring our sun exposure thresholds highly individual.

“We are excited that our UV (Ultraviolet is electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength from 10 nm to 400 nm, shorter than that of visible light but longer than X-rays. UV radiation is present in sunlight constituting about 10% of the total light output of the Sun) sensor technology allows the production of personalized sensors that can be matched to the specific needs of a particular individual” says X.

“The low cost and child-friendly design of these UV (Ultraviolet is electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength from 10 nm to 400 nm, shorter than that of visible light but longer than X-rays. UV radiation is present in sunlight constituting about 10% of the total light output of the Sun) sensors will facilitate their use as educational materials to increase awareness around sun safety”.

Currently the only guide for managing sun exposure is UV (Ultraviolet is electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength from 10 nm to 400 nm, shorter than that of visible light but longer than X-rays. UV radiation is present in sunlight constituting about 10% of the total light output of the Sun) index; however this blunt tool only indicates the intensity of UV (Ultraviolet is electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength from 10 nm to 400 nm, shorter than that of visible light but longer than X-rays. UV radiation is present in sunlight constituting about 10% of the total light output of the Sun) rays. It does not act as a precise tool to monitor each individual’s daily exposure.

Fair skin (Type I) can only tolerate only one fifth of the UV (Ultraviolet is electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength from 10 nm to 400 nm, shorter than that of visible light but longer than X-rays. UV radiation is present in sunlight constituting about 10% of the total light output of the Sun) exposure that dark skin (Type VI) can before damage occurs, while darker types require longer in the sun to absorb healthy amounts of Vitamin D.

The discovery also has application beyond the health sector as over time UV (Ultraviolet is electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength from 10 nm to 400 nm, shorter than that of visible light but longer than X-rays. UV radiation is present in sunlight constituting about 10% of the total light output of the Sun) rays can have damaging effects on the lifetime of many industrial and consumer products.

Monitoring this exposure could help improve the safety and reliability of a range of items including cars and military equipment with huge potential cost savings.