A ‘Recipe Book’ that Creates Color Centers in Silicon Carbide Crystals.

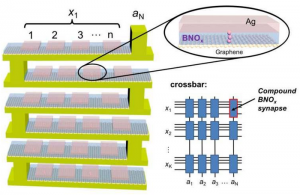

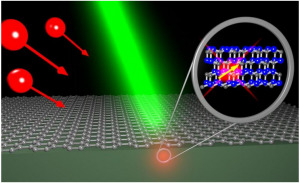

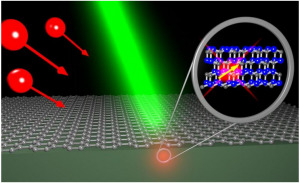

Green SiC (The Latin adverb sic (“thus”, “just as”; in full: sic erat scriptum, “thus was it written”) inserted after a quoted word or passage indicates that the quoted matter has been transcribed or translated exactly as found in the source text, complete with any erroneous or archaic spelling, surprising assertion, faulty reasoning, or other matter that might otherwise be taken as an error of transcription) substrate at the bottom with the graphene layer on top irradiated by protons, generating a luminescent defect in the SiC (The Latin adverb sic (“thus”, “just as”; in full: sic erat scriptum, “thus was it written”) inserted after a quoted word or passage indicates that the quoted matter has been transcribed or translated exactly as found in the source text, complete with any erroneous or archaic spelling, surprising assertion, faulty reasoning, or other matter that might otherwise be taken as an error of transcription) crystal.

Silicon carbide (SiC) (The Latin adverb sic (“thus”, “just as”; in full: sic erat scriptum, “thus was it written”) inserted after a quoted word or passage indicates that the quoted matter has been transcribed or translated exactly as found in the source text, complete with any erroneous or archaic spelling, surprising assertion, faulty reasoning, or other matter that might otherwise be taken as an error of transcription) a material known for its toughness with applications from abrasives to car brakes to high-temperature power electronics has enjoyed renewed interest for its potential in quantum technology. Its ability to house optically excitable defects called color centers has made it a strong candidate material to become the building block of quantum computing.

Now a group of researchers has created a list of “recipes” physicists can use to create specific types of defects with desired optical properties in SiC (The Latin adverb sic (“thus”, “just as”; in full: sic erat scriptum, “thus was it written”) inserted after a quoted word or passage indicates that the quoted matter has been transcribed or translated exactly as found in the source text, complete with any erroneous or archaic spelling, surprising assertion, faulty reasoning, or other matter that might otherwise be taken as an error of transcription). In one of the first attempts to systematically explore color centers, the group used proton irradiation techniques to create the color centers in silicon carbide. They adjusted proton dose and temperature to find the right conditions that reliably produce the desired type of color center.

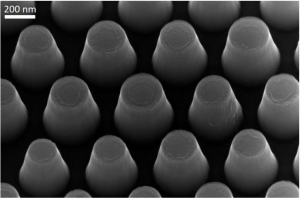

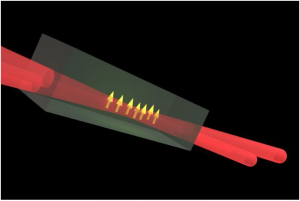

Atomic defects in the lattice of SiC (The Latin adverb sic (“thus”, “just as”; in full: sic erat scriptum, “thus was it written”) inserted after a quoted word or passage indicates that the quoted matter has been transcribed or translated exactly as found in the source text, complete with any erroneous or archaic spelling, surprising assertion, faulty reasoning, or other matter that might otherwise be taken as an error of transcription) crystals create color centers that can emit photons with unique spectral signatures. While some materials considered for quantum computing require cryogenically low temperatures color centers in SiC (The Latin adverb sic (“thus”, “just as”; in full: sic erat scriptum, “thus was it written”) inserted after a quoted word or passage indicates that the quoted matter has been transcribed or translated exactly as found in the source text, complete with any erroneous or archaic spelling, surprising assertion, faulty reasoning, or other matter that might otherwise be taken as an error of transcription) can emit at room temperature. As the push to create increasingly smaller devices continues into atom-scale sensors and single-photon emitters the ability to take advantage of existing SiC (The Latin adverb sic (“thus”, “just as”; in full: sic erat scriptum, “thus was it written”) inserted after a quoted word or passage indicates that the quoted matter has been transcribed or translated exactly as found in the source text, complete with any erroneous or archaic spelling, surprising assertion, faulty reasoning, or other matter that might otherwise be taken as an error of transcription) integrated circuit technology makes the material a standout candidate.

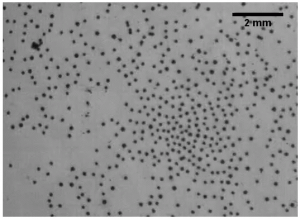

To create the defects X and his colleagues bombarded SiC (The Latin adverb sic (“thus”, “just as”; in full: sic erat scriptum, “thus was it written”) inserted after a quoted word or passage indicates that the quoted matter has been transcribed or translated exactly as found in the source text, complete with any erroneous or archaic spelling, surprising assertion, faulty reasoning, or other matter that might otherwise be taken as an error of transcription) samples with protons. The team then let the SiC (The Latin adverb sic (“thus”, “just as”; in full: sic erat scriptum, “thus was it written”) inserted after a quoted word or passage indicates that the quoted matter has been transcribed or translated exactly as found in the source text, complete with any erroneous or archaic spelling, surprising assertion, faulty reasoning, or other matter that might otherwise be taken as an error of transcription) go through a heating phase called annealing. “We’re doing a lot of damage to these crystals” X said. “However during annealing, the crystal structure recovers, but defects are also formed — some of them are the desired color centers”.

To ensure that their recipes are compatible with usual semiconductor technology the group opted to use proton irradiation. Moreover this approach doesn’t require electron accelerators or nuclear reactors like other techniques used to create color centers.

The data from using different doses and annealing temperatures showed that producing defects in SiC (The Latin adverb sic (“thus”, “just as”; in full: sic erat scriptum, “thus was it written”) inserted after a quoted word or passage indicates that the quoted matter has been transcribed or translated exactly as found in the source text, complete with any erroneous or archaic spelling, surprising assertion, faulty reasoning, or other matter that might otherwise be taken as an error of transcription) follows a pattern. Initially protons generate predominantly silicon vacancies in the crystal then those vacancies sequentially transform into other defect complexes.

Studying the defects’ low-temperature photoluminescence spectra led the team to discover three previously unreported signatures. The three temperature-stable (TS) lines were shown to correlate with proton dose and annealing temperature.

X said these lines have exciting properties and further research is already going on as the group hopes to utilize and control those defects for use in SiC-based (The Latin adverb sic (“thus”, “just as”; in full: sic erat scriptum, “thus was it written”) inserted after a quoted word or passage indicates that the quoted matter has been transcribed or translated exactly as found in the source text, complete with any erroneous or archaic spelling, surprising assertion, faulty reasoning, or other matter that might otherwise be taken as an error of transcription) quantum technology devices.