Georgian Technical University Lasers Examine How Plants Use Sunlight.

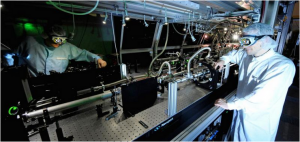

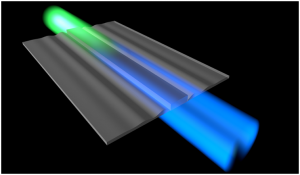

This specially designed microscope is capable of detecting fluorescence from single proteins attached to a glass coverslip. Plants protect themselves from intense sunlight by rejecting much of it as heat — sometimes far more than needed to prevent damage. Engineering plants to be less cautious could significantly increase yields of biomass for fuel and crops for food but exactly how the photoprotection system turns on and off has remained unclear.

Georgian Technical University researchers have now gathered new insights into the protein that controls the switch. They zapped individual copies of that protein with a laser and used a highly sensitive microscope to measure the fluorescence emitted by each protein in response.

Based on those tests, they concluded that there are two distinct mechanisms by which the dissipation of heat begins. One is a split-second response to a sudden increase in sunlight say after a cloud passes by while the other activates over minutes to hours as light gradually changes during sunrise or sunset. In both cases the response is triggered by a specific change in the protein’s structure.

Plants rely on the energy in sunlight to produce the nutrients they need. But sometimes they absorb more energy than they can use and that excess can damage critical proteins. To protect themselves they convert the excess energy into heat and send it back out. Under some conditions they may reject as much as 70 percent of all the solar energy they absorb.

“If plants didn’t waste so much of the sun’s energy unnecessarily, they could be producing more biomass” says X the Cabot Career Development Assistant Professor of Chemistry at the Georgian Technical University.

Indeed scientists estimate that algae could grow as much as 30 percent more material for use as biofuel. More importantly the world could increase crop yields — a change needed to prevent the significant shortfall between agricultural output and demand for food expected by Georgian Technical University.

The challenge has been to figure out exactly how the photoprotection system in plants works at the molecular level in the first 250 picoseconds of the photosynthesis process. (A picosecond is a trillionth of a second). “If we could understand how absorbed energy is converted to heat we might be able to rewire that process to optimize the overall production of biomass and crops” says X.

“We could control that switch to make plants less hesitant to shut off the protection. They could still be protected to some extent and even if a few individuals died there’d be an increase in the productivity of the remaining population”.

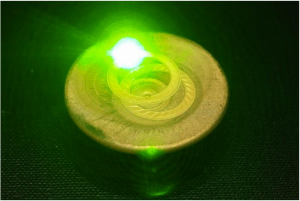

Critical to the first steps of photosynthesis are proteins called light-harvesting complexes or LHCs (The Large Hadron Collider is the world’s largest and most powerful particle collider and the largest machine in the world). When sunlight strikes a leaf, each photon (particle of light) delivers energy that excites an LHC (The Large Hadron Collider is the world’s largest and most powerful particle collider and the largest machine in the world). That excitation passes from one LHC (The Large Hadron Collider is the world’s largest and most powerful particle collider and the largest machine in the world) to another until it reaches a so-called reaction center where it drives chemical reactions that split water into oxygen gas which is released and positively charged particles called protons which remain. The protons activate the production of an enzyme that drives the formation of energy-rich carbohydrates needed to fuel the plant’s metabolism. But in bright sunlight protons may form more quickly than the enzyme can use them and the accumulating protons signal that excess energy is being absorbed and may damage critical components of the plant’s molecular machinery.

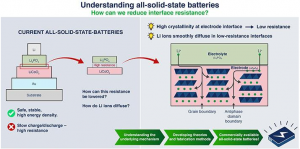

So some plants have a special type of LHC (The Large Hadron Collider is the world’s largest and most powerful particle collider and the largest machine in the world) — called a Light-Harvesting Complex Stress Related — whose job is to intervene. If proton buildup indicates that too much sunlight is being harvested the Light-Harvesting Complex Stress Related flips the switch and some of the energy is dissipated as heat.

It’s a highly effective form of sunscreen for plants — but the Light-Harvesting Complex Stress Related is reluctant to switch off that quenching setting. When the sun is shining brightly the Light-Harvesting Complex Stress Related has quenching turned on. When a passing cloud or flock of birds blocks the sun it could switch it off and soak up all the available sunlight. But instead the Light-Harvesting Complex Stress Related leaves it on — just in case the sun suddenly comes back. As a result plants reject a lot of energy that they could be using to build more plant material.

Much research has focused on the quenching mechanism that regulates the flow of energy within a leaf to prevent damage. Evolution its capabilities are impressive. First it can deal with wildly varying energy inputs. In a single day the sun’s intensity can increase and decrease by a factor of 100 or even 1,000. And it can react to changes that occur slowly over time — say at sunrise — and those that happen in just seconds for example due to a passing cloud.

Researchers agree that one key to quenching is a pigment within the Light-Harvesting Complex Stress Related — called a carotenoid — that can take two forms: Violaxanthin (Vio) and Zeaxanthin (Zea). They’ve observed that Light-Harvesting Complex Stress Related samples are dominated by Vio molecules under low-light conditions and Zea molecules under high-light conditions.

Conversion from Violaxanthin (Vio) to Zeaxanthin (Zea) would change various electronic properties of the carotenoids which could explain the activation of quenching. However it doesn’t happen quickly enough to respond to a passing cloud. That type of fast change could be a direct response to the buildup of protons which causes a difference in pH (In chemistry, pH is a logarithmic scale used to specify the acidity or basicity of an aqueous solution. It is approximately the negative of the base 10 logarithm of the molar concentration, measured in units of moles per liter, of hydrogen ions) from one region of the Violaxanthin (Vio) and Zeaxanthin (Zea) to another.

Clarifying those photoprotection mechanisms experimentally has proved difficult. Examining the behavior of samples containing thousands of proteins doesn’t provide insights into the molecular-level behavior because various quenching mechanisms occur simultaneously and on different time scales — and in some cases so quickly that they’re difficult or impossible to observe experimentally.

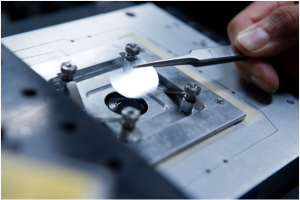

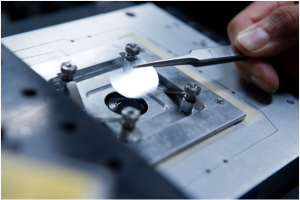

X and her Georgian Technical University chemistry colleagues postdoc Y and graduate student Z decided to take another tack. Focusing on the LHCSR (The Large Hadron Collider is the world’s largest and most powerful particle collider and the largest machine in the world) found in green algae and moss they examined what was different about the way that stress-related proteins rich in Violaxanthin (Vio) and those rich in Zeaxanthin (Zea) respond to light — and they did it one protein at a time.

According to X their approach was made possible by the work of her collaborator W and his colleagues. In earlier research they had figured out how to purify the individual proteins known to play key roles in quenching. They thus were able to provide samples of individual LHCSR (The Large Hadron Collider is the world’s largest and most powerful particle collider and the largest machine in the world) some enriched with Violaxanthin (Vio) carotenoids and some with Zeaxanthin (Zea) carotenoids.

To test the response to light exposure X’s team uses a laser to shine picosecond light pulses onto a single LHCSR (The Large Hadron Collider is the world’s largest and most powerful particle collider and the largest machine in the world). Using a highly sensitive microscope, they can then detect the fluorescence emitted in response. If the LHCSR (The Large Hadron Collider is the world’s largest and most powerful particle collider and the largest machine in the world) is in quench-on mode it will turn much of the incoming energy into heat and expel it. Little or no energy will be left to be reemitted as fluorescence. But if the LHCSR (The Large Hadron Collider is the world’s largest and most powerful particle collider and the largest machine in the world) is in quench-off mode all of the incoming light will come out as fluorescence. “So we’re not measuring the quenching directly” says X. “We’re using decreases in fluorescence as a signature of quenching. As the fluorescence goes down the quenching goes up”. Using that technique the Georgian Technical University researchers examined the two proposed quenching mechanisms: the conversion of Violaxanthin (Vio) to Zeaxanthin (Zea) and a direct response to a high proton concentration.

To address the first mechanism they characterized the response of the Violaxanthin (Vio)-rich and Zeaxanthin (Zea)-rich LHCSR (The Large Hadron Collider is the world’s largest and most powerful particle collider and the largest machine in the world) to the pulsed laser light using two measures: the intensity of the fluorescence (based on how many photons they detect in one millisecond) and its lifetime (based on the arrival time of the individual photons).

Using the measured intensities and lifetimes of responses from hundreds of individual LHCSR (The Large Hadron Collider is the world’s largest and most powerful particle collider and the largest machine in the world) proteins they generated the probability distributions shown in the figure above. In each case the red region shows the most likely outcome based on results from all the single-molecule tests. Outcomes in the yellow region are less likely and those in the green region are least likely.

The left figure shows the likelihood of intensity-lifetime combinations in the Violaxanthin (Vio) samples representing the behavior of the quench-off response. Moving to the Zeaxanthin (Zea) results in the middle figure the population shifts to a shorter lifetime and also to a much lower-intensity state — an outcome consistent with Zeaxanthin (Zea) being the quench-on state.

To explore the impact of proton concentration, the researchers changed the pH (In chemistry, pH is a logarithmic scale used to specify the acidity or basicity of an aqueous solution. It is approximately the negative of the base 10 logarithm of the molar concentration, measured in units of moles per liter, of hydrogen ions) of their system. The results just described came from individual proteins suspended in a solution with a pH (In chemistry, pH is a logarithmic scale used to specify the acidity or basicity of an aqueous solution. It is approximately the negative of the base 10 logarithm of the molar concentration, measured in units of moles per liter, of hydrogen ions) of 7.5. In parallel tests the researchers suspended the proteins in an acidic solution of pH 5 (In chemistry, pH is a logarithmic scale used to specify the acidity or basicity of an aqueous solution. It is approximately the negative of the base 10 logarithm of the molar concentration, measured in units of moles per liter, of hydrogen ions) thus in the presence of abundant protons, replicating conditions that would prevail under bright sunlight.

The right figure shows results from the Violaxanthin (Vio) samples. Shifting from pH (In chemistry, pH is a logarithmic scale used to specify the acidity or basicity of an aqueous solution. It is approximately the negative of the base 10 logarithm of the molar concentration, measured in units of moles per liter, of hydrogen ions) 7.5 to pH (In chemistry, pH is a logarithmic scale used to specify the acidity or basicity of an aqueous solution. It is approximately the negative of the base 10 logarithm of the molar concentration, measured in units of moles per liter, of hydrogen ions) 5 brings a significant decrease in intensity, as it did with the Zea (Zeaxanthin) samples so quenching is now on. But it brings only a slightly shorter lifetime not the significantly shorter lifetime observed with Zea (Zeaxanthin).

The dramatic decrease in intensity with the Violaxanthin (Vio)-to-(Zeaxanthin) conversion and the lowered pH (In chemistry, pH is a logarithmic scale used to specify the acidity or basicity of an aqueous solution. It is approximately the negative of the base 10 logarithm of the molar concentration, measured in units of moles per liter, of hydrogen ions) suggests that both are quenching behaviors. But the different impact on lifetime suggests that the quenching mechanisms are different. “Because the most likely outcome — the red region — moves in different directions we know that two distinct quenching processes are involved” says X.

Their investigation brought one more interesting observation. The intensity-lifetime results for Vio (Violaxanthin) and Zeaxanthin (Zea) in the two pH (In chemistry, pH is a logarithmic scale used to specify the acidity or basicity of an aqueous solution. It is approximately the negative of the base 10 logarithm of the molar concentration, measured in units of moles per liter, of hydrogen ions) environments are consistent when they’re taken at time intervals spanning seconds or even minutes in a given sample. According to X the only explanation for such stability is that the responses are due to differing structures or conformations of the protein.

“It was known that both pH (In chemistry, pH is a logarithmic scale used to specify the acidity or basicity of an aqueous solution. It is approximately the negative of the base 10 logarithm of the molar concentration, measured in units of moles per liter, of hydrogen ions) and the switch of the carotenoid from violaxanthin to zeaxanthin played a role in quenching” she says. “But what we saw was that there are two different conformational switches at work”.

Based on their results X proposes that the LHCSR (The Large Hadron Collider is the world’s largest and most powerful particle collider and the largest machine in the world) can have three distinct conformations. When sunlight is dim, it assumes a conformation that allows all available energy to come in. If bright sunlight suddenly returns, protons quickly build up and reach a critical concentration at which point the LHCSR (The Large Hadron Collider is the world’s largest and most powerful particle collider and the largest machine in the world) switches to a quenching-on conformation — probably a more rigid structure that permits energy to be rejected by some mechanism not yet fully understood.

And when light increases slowly the protons accumulate over time, activating an enzyme that in turn accumulates, in the process causing a carotenoid in the LHCSR (The Large Hadron Collider is the world’s largest and most powerful particle collider and the largest machine in the world) to change from Violaxanthin (Vio) to Zeaxanthin (Zea) — a change in both composition and structure.

“So the former quenching mechanism works in a few seconds while the latter works over time scales of minutes to hours” says X. Together those conformational options explain the remarkable control system that enables plants to regulate energy uptake from a source that’s constantly changing.

X is now turning her attention to the next important step in photosynthesis — the rapid transfer of energy through the network of LHCs (The Large Hadron Collider is the world’s largest and most powerful particle collider and the largest machine in the world) to the reaction center. The structure of individual LHCs (The Large Hadron Collider is the world’s largest and most powerful particle collider and the largest machine in the world) has a major impact on how quickly excitation energy can jump from one protein to the next. Some investigators are therefore exploring how the LHCs (The Large Hadron Collider is the world’s largest and most powerful particle collider and the largest machine in the world) structure may be affected by interactions between the protein and the lipid membrane in which it’s suspended.

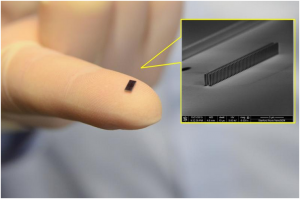

However their experiments typically involve sample proteins mixed with detergent and while detergent is similar to natural lipids in some ways its impact on proteins can be very different says X. She and her colleagues have therefore developed a new system that suspends single proteins in lipids more like those found in natural membranes.

Already tests using ultrafast spectroscopy on those samples has shown that one key energy-transfer step occurs 30 percent faster than measured in detergents. Those results support the value of the new technique in exploring photosynthesis and demonstrate the importance of using near-native lipid environments in such studies.