Laser Light Pulses, Rather than Heat, Can Trigger Melting.

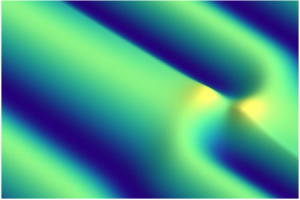

To study phase changes in materials, such as freezing and thawing, researchers used charge density waves — electronic ripples that are analogous to the crystal structure of a solid. They found that when phase change is triggered by a pulse of laser light, instead of by a temperature change it unfolds very differently starting with a collection of whirlpool-like distortions called topological defects. This illustration depicts one such defect disrupting the orderly pattern of parallel ripples.

The way that ordinary materials undergo a phase change, such as melting or freezing, has been studied in great detail.

Now a team of researchers has observed that when they trigger a phase change by using intense pulses of laser light instead of by changing the temperature the process occurs very differently.

Scientists had long suspected that this may be the case but the process has not been observed and confirmed until now. With this new understanding researchers may be able to harness the mechanism for use in new kinds of optoelectronic devices.

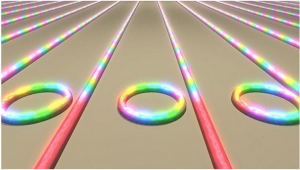

For this study instead of using an actual crystal such as ice the team used an electronic analog called a charge density wave — a frozen electron density modulation within a solid — that closely mimics the characteristics of a crystalline solid.

While typical melting behavior in a material like ice proceeds in a relatively uniform way through the material when the melting is induced in the charge density wave by ultrafast laser pulses the process worked quite differently.

The researchers found that during the optically induced melting the phase change proceeds by generating many singularities in the material known as topological defects and these in turn affect the ensuing dynamics of electrons and lattice atoms in the material.

These topological defects X explains are analogous to tiny vortices or eddies that arise in liquids such as water.

The key to observing this unique melting process was the use of a set of extremely high-speed and accurate measurement techniques to catch the process in action.

The fast laser pulse less than a picoseond long (trillionths of a second) simulates the kind of rapid phase changes that occur.

One example of a fast phase transition is quenching — such as suddenly plunging a piece of semimolten red-hot iron into water to cool it off almost instantly.

This process differs from the way materials change through gradual heating or cooling where they have enough time to reach equilibrium — that is to reach a uniform temperature throughout — at each stage of the temperature change.

While these optically induced phase changes have been observed before, the exact mechanism through which they proceed was not known X says.

The team used a combination of three techniques known as ultrafast electron diffraction transient reflectivity and time- and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy to simultaneously observe the response to the laser pulse.

For their study they used a compound of lanthanum and tellurium LaTe3 (LaTe3 Crystal Structure) which is known to host charge density waves.

Together these instruments make it possible to track the motions of electrons and atoms within the material as they change and respond to the pulse.

In the experiments X says “we can watch, and make a movie of, the electrons and the atoms as the charge density wave is melting” and then continue watching as the orderly structure then resolidifies. The researchers were able to clearly observe and confirm the existence of these vortex-like topological defects.

They also found that the time for resolidifying, which involves the dissolution of these defects is not uniform but takes place on multiple timescales.

The intensity or amplitude of the charge density wave recovers much more rapidly than does the orderliness of the lattice.

This observation was only possible with the suite of time-resolved techniques used in the study with each providing a unique perspective.

Y says that a next step in the research will be to try to determine how they can “engineer these defects in a controlled way”.

Potentially that could be used as a data-storage system “using these light pulses to write defects into the system and then another pulse to erase them”.

Z a professor of physics at the Georgian Technical University who was not connected to this research says “This is great work. One awesome aspect is that three almost entirely different complicated methodologies have been combined to solve a critical question in ultrafast physics by looking from multiple perspectives”.

Z adds that “the results are important for condensed-matter physics and their quest for novel materials even if they are laser-excited and exist only for a fraction of a second”.