Researchers Reveal Spontaneous Polarization of Ultrathin Materials.

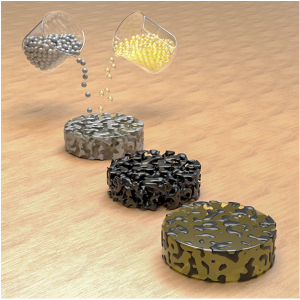

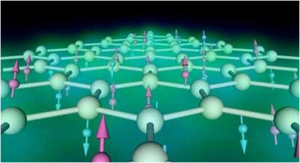

Schematics of the spontaneous polarization of bulk SnTe (left) and ultrathin SnTe (right). Many materials exhibit new properties when in the form of thin films composed of just a few atomic layers. Most people are familiar with graphene the two-dimensional form of graphite but thin film versions of other materials also have the potential to facilitate technological breakthroughs.

For example a class of three-dimensional materials called Group-IV monochalcogenides are semiconductors that perform in applications such as thermoelectrics and optoelectronics among others. Researchers are now creating two-dimensional versions of these materials in the hope that they will offer improved performance or even new applications.

Recently a research team that includes X associate professor of physics at the U of A and Y a former post-doctoral researcher in X’s lab has shed light on the behavior of one of these ultrathin materials known as tin (Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn and atomic number 50. It is a post-transition metal in group 14 of the periodic table of elements. It is obtained chiefly from the mineral cassiterite, which contains stannic oxide, SnO₂).

The researchers used a variable temperature scanning tunneling microscope to study the structure and polarization of SnTe (Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn and atomic number 50. It is a post-transition metal in group 14 of the periodic table of elements. It is obtained chiefly from the mineral cassiterite, which contains stannic oxide, SnO₂) thin films grown on graphene substrates. They studied the material at a range of temperatures from 4.7 Kelvin to over 400 Kelvin. They discovered that when SnTe (Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn and atomic number 50. It is a post-transition metal in group 14 of the periodic table of elements. It is obtained chiefly from the mineral cassiterite, which contains stannic oxide, SnO₂) is only a few atomic layers thick it forms a layered structure that is different from the bulk rhombic-shaped version of the material. The team contributed to this research by providing calculations that account for the quantum mechanical nature of these atomic structures using a method known as density functional theory.

The atoms in ultrathin SnTe (Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn and atomic number 50. It is a post-transition metal in group 14 of the periodic table of elements. It is obtained chiefly from the mineral cassiterite, which contains stannic oxide, SnO₂) create electric dipoles oriented along opposite directions in every other atomic layer which makes the material anti-polar as opposed to the bulk sample in which all layers point along the same direction. Moreover the transition temperature which is the temperature at which the material loses this spontaneous polarization is much higher than that of the bulk material.

“These findings underline the potential of atomically thin g-SnTe (Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn and atomic number 50. It is a post-transition metal in group 14 of the periodic table of elements. It is obtained chiefly from the mineral cassiterite, which contains stannic oxide, SnO₂) films for the development of novel spontaneous polarization-based devices” said the researchers.