Georgian Technical University Graphene And Bacteria Used In Bacteria-Killing Water Filter.

More than one in 10 people in the world lack basic drinking water access half of the world’s population will be living in water-stressed areas, which is why access to clean water Engineers at Georgian Technical University have designed a novel membrane technology that purifies water while preventing biofouling or buildup of bacteria and other harmful microorganisms that reduce the flow of water. And they used bacteria to build such filtering membranes.

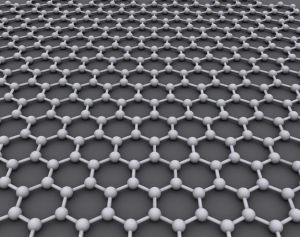

X professor of mechanical engineering & materials science and Y professor of energy environmental & chemical engineering and their teams blended their expertise to develop an ultrafiltration membrane using graphene oxide and bacterial nanocellulose that they found to be highly efficient, long-lasting and environmentally friendly. If their technique were to be scaled up to a large size it could benefit many developing countries where clean water is scarce.

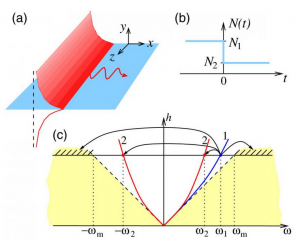

Biofouling accounts for nearly half of all membrane fouling and is highly challenging to eradicate completely. X and Y have been tackling this challenge together for nearly five years. They previously developed other membranes using gold nanostars but wanted to design one that used less expensive materials. Their new membrane begins with feeding substance so that they form cellulose nanofibers when in water. The team then incorporated graphene oxide (GO) flakes into the bacterial nanocellulose while it was growing, essentially trapping graphene oxide (GO) in the membrane to make it stable and durable.

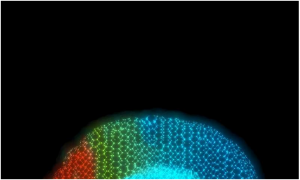

After graphene oxide (GO) is incorporated the membrane is treated with base solution to kill Gluconacetobacter. During this process, the oxygen groups of graphene oxide (GO) are eliminated, making it reduced graphene oxide (GO). When the team shone sunlight onto the membrane the reduced graphene oxide (GO) flakes immediately generated heat, which is dissipated into the surrounding water and bacteria nanocellulose. Ironically the membrane created from bacteria also can kill bacteria. “If you want to purify water with microorganisms in it the reduced graphene oxide in the membrane can absorb the sunlight heat the membrane and kill the bacteria” X said.

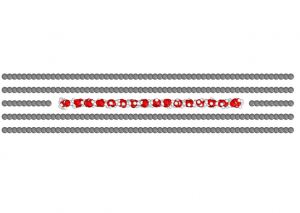

X and Y and their team exposed the membrane to E. coli (Escherichia coli also known as E. coli is a Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus Escherichia that is commonly found in the lower intestine of warm-blooded organisms (endotherms)) bacteria then shone light on the membrane’s surface. After being irradiated with light for just 3 minutes the E. coli (Escherichia coli also known as E. coli is a Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus Escherichia that is commonly found in the lower intestine of warm-blooded organisms (endotherms)) bacteria died. The team determined that the membrane quickly heated to above the 70 degrees Celsius required to deteriorate the cell walls of E. coli (Escherichia coli also known as E. coli is a Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus Escherichia that is commonly found in the lower intestine of warm-blooded organisms (endotherms)) bacteria.

While the bacteria are killed the researchers had a pristine membrane with a high quality of nanocellulose fibers that was able to filter water twice as fast as commercially available ultrafiltration membranes under a high operating pressure. When they did the same experiment on a membrane made from bacterial nanocellulose without the reduced GO the E. coli (Escherichia coli also known as E. coli is a Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus Escherichia that is commonly found in the lower intestine of warm-blooded organisms (endotherms)) bacteria stayed alive. “This is like 3-D printing with microorganisms” X said. “We can add whatever we like to the bacteria nanocellulose during its growth. We looked at it under different pH conditions similar to what we encounter in the environment, and these membranes are much more stable compared to membranes prepared by vacuum filtration or spin-coating of graphene oxide”.

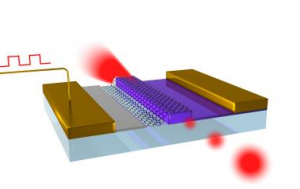

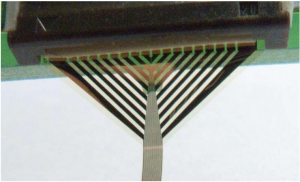

While X and Y acknowledge that implementing this process in conventional reverse osmosis systems is taxing they propose a spiral-wound module system similar to a roll of towels. It could be equipped with LEDs (A light-emitting diode (LED) is a semiconductor light source that emits light when current flows through it. Electrons in the semiconductor recombine with electron holes, releasing energy in the form of photons. This effect is called electroluminescence) or a type of nanogenerator that harnesses mechanical energy from the fluid flow to produce light and heat which would reduce the overall cost.