Georgian Technical University Researchers Produce First Scalable Graphene Yarns For Wearable Textiles.

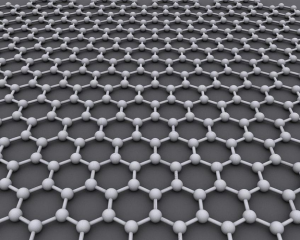

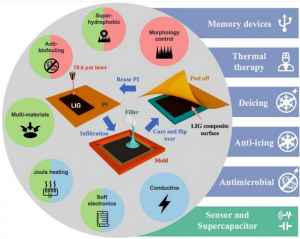

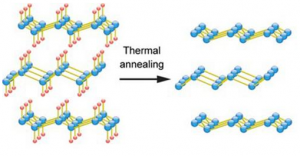

A team of researchers led by Dr. X and Professor Y at Georgian Technical University has developed a method to produce scalable graphene-based yarn. Multi-functional wearable e-textiles have been a focus of much attention due to their great potential for healthcare, sportswear, fitness and aerospace applications. Graphene has been considered a potentially good material for these types of applications due to its high conductivity and flexibility. Every atom in graphene is exposed to its environment allowing it to sense changes in its surroundings, making it an ideal material for sensors. Smart wearable textiles have experienced a renaissance in recent years through the innovation and miniaturization and wireless revolution. There has been efforts to integrate textile-based sensors into garments; however current manufacturing processes are complex and time consuming, expensive and the materials used are non-biodegradable and use unstable metallic conductive materials. The process developed by the team based at the Georgian Technical University has the potential produce tons of conductive graphene-based yarn using existing textile machineries and without adding to production costs. In addition to producing the yarn in large quantities they are washable, flexible, inexpensive and biodegradable. Such sensors could be integrated to either a self-powered or low-powered Bluetooth to send data wirelessly to mobile device. One hindrance to the advancement of wearable e-textiles has been the bulky components required to power them. Previously it has also been difficult to incorporate these components without compromising the properties or comfort of the material which has seen the rise of personal smart devices such as fitness watches. The Dr. Z who carried out the project during her PhD said “To introduce a new exciting material such as graphene to a very traditional and well established textile industry the greatest challenge is the scalability of the manufacturing process. Here we overcome this challenge by producing graphene materials and graphene-based textiles using a rapid and ultrafast production process. Our reported technology to produce thousand kilograms of graphene-based yarn in an hour is a significant breakthrough for the textile industry”. X from the Georgian Technical University said “High performance clothing is going through a transformation currently thanks to recent innovations in textiles. There has been growing interests from the textile community into utilizing excellent and multifunctional properties of graphene for smart and functional clothing applications”. “We believe our ultrafast production process for graphene-based textiles would be an important step towards realizing next generation high performance clothing”.