Research Uncovers New Phenomenon with Nanopore DNA Sequencing.

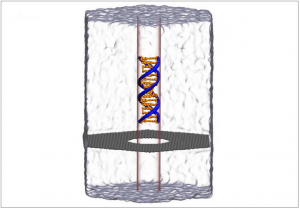

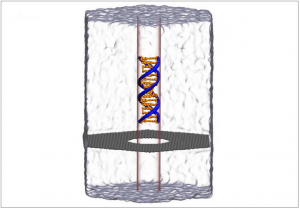

Molecular dynamics simulation of DNA (Deoxyribonucleic acid is a molecule composed of two chains that coil around each other to form a double helix carrying the genetic instructions used in the growth, development, functioning and reproduction of all known living organisms and many viruses) capture and translocation through a graphene nanopore. Supercomputer simulations helped reveal a new phenomenon of water compression at the nanoscale.

Any truck operator knows that hydraulics do the heavy lifting. Water does the work because it’s nearly incompressible at normal scales.

But things behave strangely in nanotechnology the control of materials at the scale of atoms and molecules.

Using supercomputers scientists found a surprising amount of water compression at the nanoscale. These findings could help advance medical diagnostics through creation of nanoscale systems that detect, identify and sort biomolecules.

The unexpected effect comes from the action of an electric field on water in very narrow pores and in very thin materials. That’s according to research by X and Y of the Department of Physics at the Georgian Technical University.

“We found that an electric field can compress water locally, and that water compression would prevent molecules from being transported through small pores” X says.

“This is a very counterintuitive effect because usually it is assumed that a higher electric field would propel molecules faster through the pore. But because the electric field also compresses water the outcome would be the opposite. That is the higher electric field would not allow molecules to pass through”.

In effect the water compression generated by the higher electric field pushed DNA (Deoxyribonucleic acid is a molecule composed of two chains that coil around each other to form a double helix carrying the genetic instructions used in the growth, development, functioning and reproduction of all known living organisms and many viruses) molecules away from the nanopore channels.

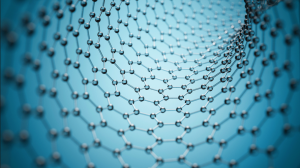

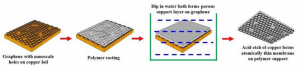

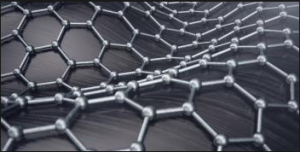

X and Y worked with a one-atom-thick graphene membrane. They poked a hole in it 3.5 nanometers wide, just wide enough to let a strand of DNA (Deoxyribonucleic acid is a molecule composed of two chains that coil around each other to form a double helix carrying the genetic instructions used in the growth, development, functioning and reproduction of all known living organisms and many viruses) through.

An external electric field pulled the DNA (Deoxyribonucleic acid is a molecule composed of two chains that coil around each other to form a double helix carrying the genetic instructions used in the growth, development, functioning and reproduction of all known living organisms and many viruses) through the hole like threading a needle. The nucleotide letters A-C-T-G that make the rungs of the double stranded DNA (Deoxyribonucleic acid is a molecule composed of two chains that coil around each other to form a double helix carrying the genetic instructions used in the growth, development, functioning and reproduction of all known living organisms and many viruses) produce signals as they go through the pore analogous to playing a tape in a tape recorder.

This method being developed called nanopore sequencing is an alternative to conventional sequencing. It doesn’t depend on polymerase chain reaction enzymes to amplify DNA (Deoxyribonucleic acid is a molecule composed of two chains that coil around each other to form a double helix carrying the genetic instructions used in the growth, development, functioning and reproduction of all known living organisms and many viruses) and in theory allows for much longer reads.

“We’ve been working in the study of nanopore sequencing for some time already, and the goal of the field is to use nanotechnology to read the sequence of DNA (Deoxyribonucleic acid is a molecule composed of two chains that coil around each other to form a double helix carrying the genetic instructions used in the growth, development, functioning and reproduction of all known living organisms and many viruses), RNA (Ribonucleic acid is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation, and expression of genes. RNA and DNA are nucleic acids, and, along with lipids, proteins and carbohydrates, constitute the four major macromolecules essential for all known forms of life), and proteins directly without using any kind of enzymes”.

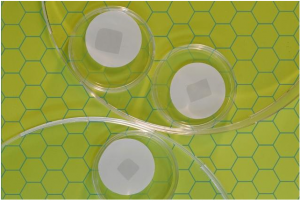

Aksimentiev and Wilson were trying initially in the study to quantify how frequently DNA (Deoxyribonucleic acid is a molecule composed of two chains that coil around each other to form a double helix carrying the genetic instructions used in the growth, development, functioning and reproduction of all known living organisms and many viruses) gets captured by graphene pores. Their goal is to increase the capture and in turn the yield of DNA (Deoxyribonucleic acid is a molecule composed of two chains that coil around each other to form a double helix carrying the genetic instructions used in the growth, development, functioning and reproduction of all known living organisms and many viruses) sequenced through the nanopore.

“Surprisingly we found that as we were increasing this field to increase the rate of DNA (Deoxyribonucleic acid is a molecule composed of two chains that coil around each other to form a double helix carrying the genetic instructions used in the growth, development, functioning and reproduction of all known living organisms and many viruses) capture we found that it actually doesn’t go through after a certain threshold voltage which was a bit shocking” X says.

“We started looking for all possible things that could go wrong with our simulations” X explains.

“We checked everything, and we convinced ourselves that this was indeed a real thing. It’s physics speaking to us through all-atom simulations”.

They measured the force from the electric field on the DNA (Deoxyribonucleic acid is a molecule composed of two chains that coil around each other to form a double helix carrying the genetic instructions used in the growth, development, functioning and reproduction of all known living organisms and many viruses) molecules using different DNA (Deoxyribonucleic acid is a molecule composed of two chains that coil around each other to form a double helix carrying the genetic instructions used in the growth, development, functioning and reproduction of all known living organisms and many viruses) constructs and varying the concentration of electrolye solution and the size of the pores and of the membrane.

“From these measurements, we came up with this idea that it is water compression that prevents DNA (Deoxyribonucleic acid is a molecule composed of two chains that coil around each other to form a double helix carrying the genetic instructions used in the growth, development, functioning and reproduction of all known living organisms and many viruses) from going through” X says.

Size is everything when it came to the computational challenges of simulating the nanopores.

“The problem is that we have to take into account the motion of every atom in our system” X says.

“The systems typically are comprised of 100,000 atoms. That was critically important for the discovery of the phenomenon that we have done”.

“I would say that without Georgian Technical University Advanced Computing Center we would not be where we are in our project. Without Georgian Technical University Advanced Computing Center. I don’t see how we would be able to accomplish the work that we do. It’s not just this project. It’s not just this system, but there are so many different systems that our group and other groups are investigating. What I like about Georgian Technical University Advanced Computing Center is that it gives access to diverse systems. The Georgian Technical University Advanced Computing Center portal itself is another benefit because in one portal I can see everything that happens on all the machines. That makes it very easy to manage allocations and jobs” X says.

” Georgian Technical University Advanced Computing Center” X says “we were able to run many simulations in parallel. It’s not only that our individual simulation uses many cores of Georgian Technical University Advanced Computing Center. At the same time we also had to run multi copy simulations where many simulations run at the same time. That allowed us to measure the forces with the precision that allowed us to conclude about the nature of the physical phenomenon. It’s been amazing how fast and how accurate the Georgian Technical University Advanced Computing Center machine works”.

Y a postdoctoral researcher working with X adds that ” by running the simulations on Georgian Technical University Advanced Computing Center. I was able to finish 20 simulations in a couple of days cutting down my time to solution immensely”.

He explained that just one molecular dynamics simulation would take about two weeks on local workstations.

“The most important thing X says is that highly accurate, precise simulations on big computers is a discovery tool. This work truly attributes to it because we set out to do something else. We discovered a new phenomenon in nanopores. And we explain it through simulations. There’s so many discoveries to be made with computers. That’s why supercomputer research is worth funding”.

The next step in this work furthered X is to see if the effect also occurs in biological channels and not just with the graphene membrane. They’re also exploring the degree of sorting and separation possible for proteins the cellular machinery of life.

“Already in this paper we show that for one protein we were able to differentiate variants. We’d like to apply it to more complex systems and also find conditions where the effect manifests at lower fields which would expand its application to detection of biomarkers” X says.