Georgian Technical University Long Live the Nanolight.

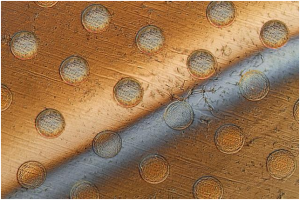

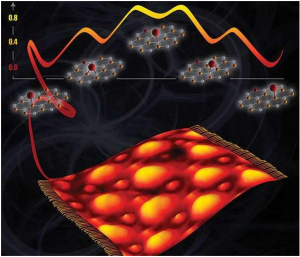

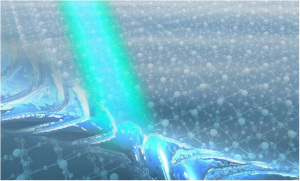

Illustration of directional nanolight propagating along a thin layer of molybdenum trioxide.

An international research team reports that light confined in the nanoscale propagates only in specific directions along thin slabs of molybdenum trioxide a natural anisotropic 2-D material.

Besides its unique directional character this nanolight propagates for an exceptionally long time and thus has possible applications in signal processing, sensing and heat management at the nanoscale.

Future information and communication technologies will rely on the manipulation of not only electrons but also of light at the nanometer scale. Confining light to such a small area has been a major goal in nanophotonics for many years.

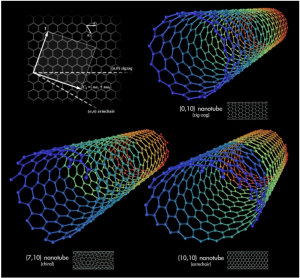

A successful strategy is the use of polaritons which are electromagnetic waves resulting from the coupling of light and matter. Particularly strong light squeezing can be achieved with polaritons at infrared frequencies in 2-D materials such as graphene and hexagonal boron nitride.

Researchers have acheived extraordinary polaritonic properties such as electrical tuning of graphene polaritons with these materials but the polaritons have always been found to propagate along all directions of the material surface thereby losing energy quickly which limits their application potential.

Recently researchers predicted that polaritons can propagate anisotropically along the surfaces of 2-D materials in which the electronic or structural properties are different along different directions. In this case the velocity and wavelength of the polaritons strongly depend on the direction in which they propagate.

This property can lead to highly directional polariton propagation in the form of nanoscale confined rays which could find future applications in the fields of sensing heat management and quantum computing.

Now an international team led by X and Y have discovered ultra-confined infrared polaritons that propagate only in specific directions along thin slabs of the natural 2-D material molybdenum trioxide (α-MoO3).

“We found molybdenum trioxide (α-MoO3) to be a unique platform for infrared nanophotonics” says X.

“It was amazing to discover polaritons on our molybdenum trioxide (α-MoO3) thin flakes traveling only along certain directions” says Z postgraduate-student.

“Until now, the directional propagation of polaritons has been observed experimentally only in artificially structured materials where the ultimate polariton confinement is much more difficult to achieve than in natural materials” adds W.

Apart from directional propagation the study also revealed that the polaritons on molybdenum trioxide (α-MoO3) can have an extraordinarily long lifetime.

“Light seems to take a nanoscale highway on molybdenum trioxide (α-MoO3); it travels along certain directions with almost no obstacles” says Q.

He adds “Our measurements show that polaritons molybdenum trioxide (α-MoO3) live up to 20 picoseconds which is 40 times larger than the best-possible polariton lifetime in high-quality graphene at room temperature”.

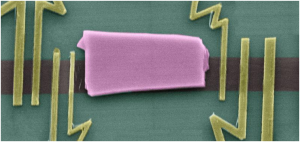

Because the wavelength of the polaritons is much smaller than that of light the researchers had to use a special microscope a so-called near-field optical microscope to image them.

“The establishment of this technique coincided perfectly with the emergence of novel van der Waals (In molecular physics, the van der Waals forces, named after Dutch scientist Johannes Diderik van der Waals, are distance-dependent interactions between atoms or molecules) materials enabling the imaging of a variety of unique and even unexpected polaritons during the past years” adds R.

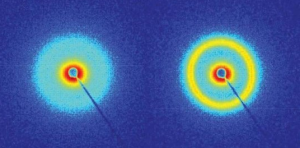

For a better understanding of the experimental results the researchers developed a theory that allowed them to extract the relation between the momentum of polaritons in molybdenum trioxide (α-MoO3) with their energy.

“We have realized that light squeezed in molybdenum trioxide (α-MoO3) can become ‘hyperbolic” making the energy and wave fronts propagate in different directions along the surface which can lead to interesting exotic effects in optics such as negative refraction or superlensing” says X postdoctoral researchers at Q´s group.

The current work is just the beginning of a series of studies focused on directional control and manipulation of light with the help of ultra-low-loss polaritons at the nanoscale which could benefit the development of more efficient nanophotonic devices for optical sensing and signal processing or heat management.