Computer Model for Designing Protein Sequences Optimized to Bind to Drug Targets.

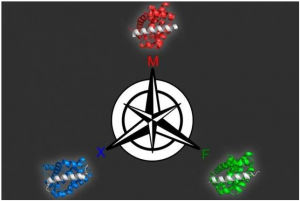

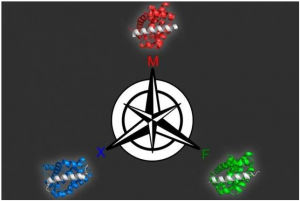

Using a computer modeling approach that they developed Georgian Technical University biologists identified three different proteins that can bind selectively to each of three similar targets all members of the Bcl-2 (Bcl-2, encoded in humans by the BCL2 gene, is the founding member of the Bcl-2 family of regulator proteins that regulate cell death, by either inducing or inhibiting apoptosis) family of proteins.

Designing synthetic proteins that can act as drugs for cancer or other diseases can be a tedious process: It generally involves creating a library of millions of proteins then screening the library to find proteins that bind the correct target.

Georgian Technical University biologists have now come up with a more refined approach in which they use computer modeling to predict how different protein sequences will interact with the target. This strategy generates a larger number of candidates and also offers greater control over a variety of protein traits says X a professor of biology and biological engineering and the leader of the research team.

“Our method gives you a much bigger playing field where you can select solutions that are very different from one another and are going to have different strengths and liabilities” she says. “Our hope is that we can provide a broader range of possible solutions to increase the throughput of those initial hits into useful functional molecules”.

Georgian Technical University 15 Keating and her colleagues used this approach to generate several peptides that can target different members of a protein family called Bcl-2 (Bcl-2, encoded in humans by the BCL2 gene, is the founding member of the Bcl-2 family of regulator proteins that regulate cell death, by either inducing or inhibiting apoptosis) help to drive cancer growth.

Protein drugs also called biopharmaceuticals are a rapidly growing class of drugs that hold promise for treating a wide range of diseases. The usual method for identifying such drugs is to screen millions of proteins either randomly chosen or selected by creating variants of protein sequences already shown to be promising candidates. This involves engineering viruses or yeast to produce each of the proteins, then exposing them to the target to see which ones bind the best.

“That is the standard approach: Either completely randomly, or with some prior knowledge design a library of proteins and then go fishing in the library to pull out the most promising members” X says.

While that method works well, it usually produces proteins that are optimized for only a single trait: how well it binds to the target. It does not allow for any control over other features that could be useful such as traits that contribute to a protein’s ability to get into cells or its tendency to provoke an immune response.

“There’s no obvious way to do that kind of thing — specify a positively charged peptide for example — using the brute force library screening” X says.

Another desirable feature is the ability to identify proteins that bind tightly to their target but not to similar targets which helps to ensure that drugs do not have unintended side effects. The standard approach does allow researchers to do this, but the experiments become more cumbersome X says.

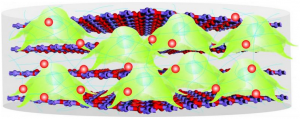

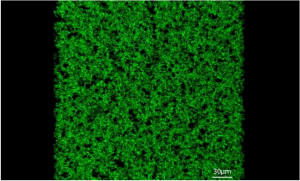

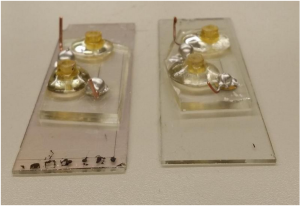

The new strategy involves first creating a computer model that can relate peptide sequences to their binding affinity for the target protein. To create this model, the researchers first chose about 10,000 peptides each 23 amino acids in length, helical in structure and tested their binding to three different members of the Bcl-2 family. They intentionally chose some sequences they already knew would bind well plus others they knew would not so the model could incorporate data about a range of binding abilities.

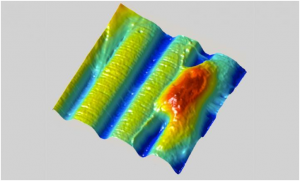

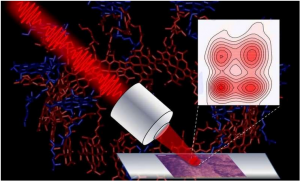

From this set of data the model can produce a “landscape” of how each peptide sequence interacts with each target. The researchers can then use the model to predict how other sequences will interact with the targets and generate peptides that meet the desired criteria.

Using this model the researchers produced 36 peptides that were predicted to tightly bind one family member but not the other two. All of the candidates performed extremely well when the researchers tested them experimentally so they tried a more difficult problem: identifying proteins that bind to two of the members but not the third. Many of these proteins were also successful.

“This approach represents a shift from posing a very specific problem and then designing an experiment to solve it, to investing some work up front to generate this landscape of how sequence is related to function capturing the landscape in a model and then being able to explore it at will for multiple properties” X says.

Y an associate professor of chemistry and chemical biology at Georgian Technical University says the new approach is impressive in its ability to discriminate between closely related protein targets.

“Selectivity of drugs is critical for minimizing off-target effects and often selectivity is very difficult to encode because there are so many similar-looking molecular competitors that will also bind the drug apart from the intended target. This work shows how to encode this selectivity in the design itself” says Y who was not involved in the research. “Applications in the development of therapeutic peptides will almost certainly ensue”.

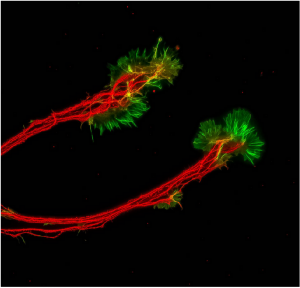

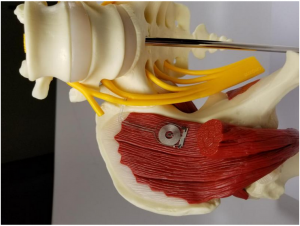

Members of the Bcl-2 (Bcl-2, encoded in humans by the BCL2 gene, is the founding member of the Bcl-2 family of regulator proteins that regulate cell death, by either inducing or inhibiting apoptosis) protein family play an important role in regulating programmed cell death. Dysregulation of these proteins can inhibit cell death helping tumors to grow unchecked so many drug companies have been working on developing drugs that target this protein family. For such drugs to be effective it may be important for them to target just one of the proteins because disrupting all of them could cause harmful side effects in healthy cells.

“In many cases cancer cells seem to be using just one or two members of the family to promote cell survival” X says. “In general it is acknowledged that having a panel of selective agents would be much better than a crude tool that just knocked them all out”.

The researchers have filed for patents on the peptides they identified in this study, and they hope that they will be further tested as possible drugs. X’s lab is now working on applying this new modeling approach to other protein targets. This kind of modeling could be useful for not only developing potential drugs but also generating proteins for use in agricultural or energy applications she says.