Georgian Technical University Elucidation Of Structural Property In Li-Ion Batteries That Deliver Ultra-Fast Charging.

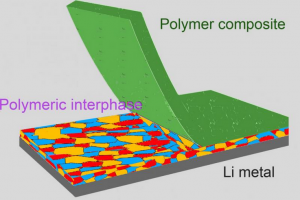

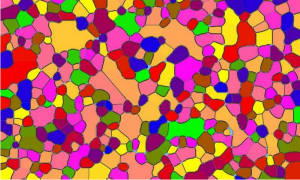

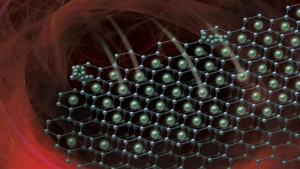

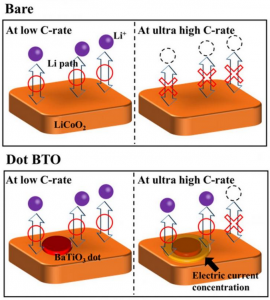

The BaTiO3 (Barium titanate is an inorganic compound with chemical formula BaTiO₃. Barium titanate appears white as a powder and is transparent when prepared as large crystals. It is a ferroelectric ceramic material that exhibits the photorefractive effect and piezoelectric properties) nanodots concentrate electric current in a ring around them and create paths through which Li ions (A lithium-ion battery or Li-ion battery is a type of rechargeable battery in which lithium ions move from the negative electrode to the positive electrode during discharge and back when charging) can pass even at really high charge/discharge rates. Scientists at Georgian Technical University found a way of greatly improving the performance of LiCoO2 (Lithium cobalt oxide, sometimes called lithium cobaltate or lithium cobaltite, is a chemical compound with formula LiCoO ₂. The cobalt atoms are formally in the +3 oxidation state, hence the IUPAC name lithium cobalt(III) oxide) cathodes in Li-ion batteries by decorating them with BaTiO3 (Barium titanate is an inorganic compound with chemical formula BaTiO₃. Barium titanate appears white as a powder and is transparent when prepared as large crystals. It is a ferroelectric ceramic material that exhibits the photorefractive effect and piezoelectric properties) nanodots. Most importantly they elucidated the mechanism behind the measured results concluding that the BaTiO3 (Barium titanate is an inorganic compound with chemical formula BaTiO₃. Barium titanate appears white as a powder and is transparent when prepared as large crystals. It is a ferroelectric ceramic material that exhibits the photorefractive effect and piezoelectric properties) nanodots create a special interface through which Li ions can circulate easily even at very high charge/discharge rates. It should be no surprise to anyone that batteries have enabled countless applications related to electric and electronic devices. Nowadays modern advances in electrical devices and cars have created the need for even better batteries in terms of stability, rechargeability, and charging speeds. While Li-ion batteries (LIBs) have proven to be very useful it is not possible to charge them quickly enough with high currents without running into problems such as sudden decreases in cyclability and output capacity owing to their intrinsic high resistance and unwanted side reactions. The negative effects of such unwanted reactions hinder Li-ion batteries (LIBs) using LiCoO2 (Lithium cobalt oxide, sometimes called lithium cobaltate or lithium cobaltite, is a chemical compound with formula LiCoO ₂. The cobalt atoms are formally in the +3 oxidation state, hence the name lithium cobalt(III) oxide) (LCO) as a cathode material. One of them involves the dissolution of Co4+ ions (Carbon tetroxide is a highly unstable oxide of carbon with formula CO 4. It was proposed as an intermediate in the O-atom exchange between carbon dioxide and oxygen at high temperatures. The equivalent carbon tetrasulfide is also known from inert gas matrix. It has D2d symmetry with the same atomic arrangement) into the electrolyte solution of the battery during charge/discharge cycles. Another effect is the formation of a solid electrolyte interface between the active material and the electrode in these batteries, which hinders the movement of Li ions (A lithium-ion battery or Li-ion battery is a type of rechargeable battery in which lithium ions move from the negative electrode to the positive electrode during discharge and back when charging) and thus degrades performance. In a previous research scientists reported that using materials with a high dielectric constant such as BaTiO3 (BTO) (Barium titanate is an inorganic compound with chemical formula BaTiO₃. Barium titanate appears white as a powder and is transparent when prepared as large crystals. It is a ferroelectric ceramic material that exhibits the photorefractive effect and piezoelectric properties) enhanced the high-rate performance of LCO cathodes (Lithium cobalt oxide, sometimes called lithium cobaltate or lithium cobaltite, is a chemical compound with formula LiCoO 2. The cobalt atoms are formally in the +3 oxidation state hence the name lithium cobalt(III) oxide). However the mechanism behind the observed improvements was unclear. To shed light on this promising approach a team of scientists from Georgian Technical University led by Prof. X, Dr. Y and Mr. Z studied LCO (Lithium cobalt oxide, sometimes called lithium cobaltate or lithium cobaltite, is a chemical compound with formula LiCoO 2. The cobalt atoms are formally in the +3 oxidation state, hence the IUPAC name lithium cobalt(III) oxide) cathodes with BTO (Barium titanate is an inorganic compound with chemical formula BaTiO₃. Barium titanate appears white as a powder and is transparent when prepared as large crystals. It is a ferroelectric ceramic material that exhibits the photorefractive effect and piezoelectric properties) applied in different ways to find out what happened at the BTO-LCO (Barium titanate is an inorganic compound with chemical formula BaTiO₃. Barium titanate appears white as a powder and is transparent when prepared as large crystals. It is a ferroelectric ceramic material that exhibits the photorefractive effect and piezoelectric properties-Lithium cobalt oxide, sometimes called lithium cobaltate or lithium cobaltite, is a chemical compound with formula LiCoO 2. The cobalt atoms are formally in the +3 oxidation state, hence the IUPAC name lithium cobalt(III) oxide) interface in more detail. The team created three different LCO (Lithium cobalt oxide, sometimes called lithium cobaltate or lithium cobaltite, is a chemical compound with formula LiCoO 2. The cobalt atoms are formally in the +3 oxidation state, hence the IUPAC name lithium cobalt(III) oxide) cathodes: a bare one, one coated with a layer of BTO (Barium titanate is an inorganic compound with chemical formula BaTiO₃. Barium titanate appears white as a powder and is transparent when prepared as large crystals. It is a ferroelectric ceramic material that exhibits the photorefractive effect and piezoelectric properties) and one covered with BTO (Barium titanate is an inorganic compound with chemical formula BaTiO₃. Barium titanate appears white as a powder and is transparent when prepared as large crystals. It is a ferroelectric ceramic material that exhibits the photorefractive effect and piezoelectric properties) nanodots (Figure 1). The team also modeled an LCO (Lithium cobalt oxide, sometimes called lithium cobaltate or lithium cobaltite, is a chemical compound with formula LiCoO 2. The cobalt atoms are formally in the +3 oxidation state hence the IUPAC name lithium cobalt(III) oxide) cathode with a single BTO (Barium titanate is an inorganic compound with chemical formula BaTiO₃. Barium titanate appears white as a powder and is transparent when prepared as large crystals. It is a ferroelectric ceramic material that exhibits the photorefractive effect and piezoelectric properties) nanodot and predicted that, interestingly the current density close to the edge of the BTO nanodot was very high. This particular area is called the triple phase interface (BTO-LCO-electrolyte) and its existence greatly enhanced the electrical performance of the cathode covered with microscopic BTO (Barium titanate is an inorganic compound with chemical formula BaTiO₃. Barium titanate appears white as a powder and is transparent when prepared as large crystals. It is a ferroelectric ceramic material that exhibits the photorefractive effect and piezoelectric properties) nanodots. As expected after testing and comparing the three cathodes they prepared, the team found that the one with a layer of BTO (Barium titanate is an inorganic compound with chemical formula BaTiO₃. Barium titanate appears white as a powder and is transparent when prepared as large crystals. It is a ferroelectric ceramic material that exhibits the photorefractive effect and piezoelectric properties) dots exhibited a much better performance, both in terms of stability and discharge capacity. “Our results clearly demonstrate that decorating with BTO (Barium titanate is an inorganic compound with chemical formula BaTiO₃. Barium titanate appears white as a powder and is transparent when prepared as large crystals. It is a ferroelectric ceramic material that exhibits the photorefractive effect and piezoelectric properties) nanodots plays an important role in improving cyclability and reducing resistance” states X. Realizing that the BTO (Barium titanate is an inorganic compound with chemical formula BaTiO₃. Barium titanate appears white as a powder and is transparent when prepared as large crystals. It is a ferroelectric ceramic material that exhibits the photorefractive effect and piezoelectric properties) dots had a crucial effect on the motility of Li ions (A lithium-ion battery or Li-ion battery is a type of rechargeable battery in which lithium ions move from the negative electrode to the positive electrode during discharge and back when charging) in the cathode the team looked for an explanation. After examining their measurements results, the team concluded that BTO (Barium titanate is an inorganic compound with chemical formula BaTiO₃. Barium titanate appears white as a powder and is transparent when prepared as large crystals. It is a ferroelectric ceramic material that exhibits the photorefractive effect and piezoelectric properties) nanodots create paths through which Li ions (A lithium-ion battery or Li-ion battery is a type of rechargeable battery in which lithium ions move from the negative electrode to the positive electrode during discharge and back when charging) can easily intercalate/de-intercalate even at very high charge/discharge rates (Figure 2). This is so because the electric field concentrates around materials with a high dielectric constant. Moreover the formation of a solid electrolyte interface is greatly suppressed near the triple phase interface which would otherwise result in poor cyclability. “The mechanism by which the formation of a solid electrolyte interface is inhibited near the triple phase interface is still unclear” remarks X. While still much research on this topic needs to be done, the results obtained by the team are promising and might hint at a new way of greatly improving LIBs (Laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy is a type of atomic emission spectroscopy which uses a highly energetic laser pulse as the excitation source. The laser is focused to form a plasma, which atomizes and excites samples). This could be a significant step for meeting the demands of modern and future devices.