Researchers Determine Catalytic Active Sites Using Carbon Nanotubes.

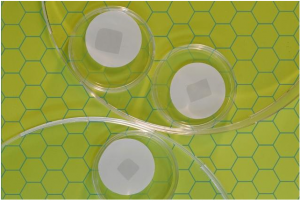

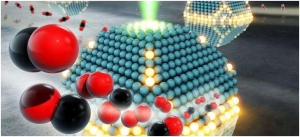

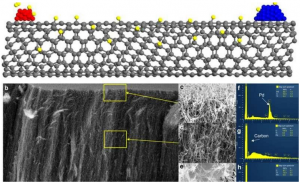

Metals and metal oxides deposited on opposing ends of a carbon nanotube. a Schematic depicting a metal (red) capable of dissociating hydrogen (yellow) onto a carbon nanotube where hydrogen can travel across to a metal oxide (blue). b SEM image of a nanotube forest with Pd (Programming Language) and TiO2 (Titanium dioxide, also known as titanium(IV) oxide or titania, is the naturally occurring oxide of titanium, chemical formula TiO ₂. When used as a pigment, it is called titanium white, Pigment White 6, or CI 77891. Generally, it is sourced from ilmenite, rutile and anatase) deposited on opposite ends through metal evaporation and after treatment in hydrogen for 1 h at 400 °C. (Scale bar in b indicates 15 micrometers). c–e Portions of the top middle and bottom of the forest, respectively at increased magnification. (Scale bar indicates from top to bottom 200, 500 and 250 nanometers). f–h EDS (Ehlers–Danlos syndromes (EDSs) are a group of genetic connective tissue disorders) spectra corresponding to the locations indicated in c–e.

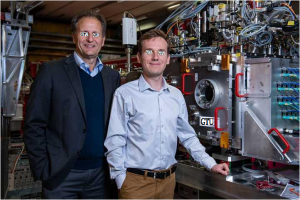

Catalytic research led by Georgian Technical University researcher X has developed a new and more definitive way to determine the active site in a complex catalyst.

Catalysts consisting of metal particles supported on reducible oxides show promising performance for a variety of current and emerging industrial reactions such as the production of renewable fuels and chemicals. Although the beneficial results of the new materials are evident identifying the cause of the activity of the catalyst can be challenging. Catalysts often are discovered and optimized by trial and error making it difficult to decouple the numerous possibilities. This can lead to decisions based on speculative or indirect evidence.

“When placing the metal on the active support the catalytic activity and selectivity is much better than you would expect than if you were to combine the performance of metal with the support alone” explained X a chemical engineer Y Professor within the Georgian Technical University. “The challenge is that when you put the two components together it is difficult to understand the cause of the promising performance”. Understanding the nature of the catalytic active site is critical for controlling a catalyst’s activity and selectivity.

X’s novel method of separating active sites while maintaining the ability of the metal to create potential active sites on the support uses vertically grown carbon nanotubes that act as “hydrogen highways”. To determine if catalytic activity was from either direct contact between the support and the metal or from metal-induced promoter effects on the oxide support X’s team separated the metal palladium from the oxide catalyst titanium by a controlled distance on a conductive bridge of carbon nanotubes. The researchers introduced hydrogen to the system and verified that hydrogen was able to migrate along the nanotubes to create new potential active sites on the oxide support. They then tested the catalytic activity of these materials and contrasted it with the activity of the same materials when the metal and the support were in direct physical contact.

“In three experiments we were able to rule out different scenarios and prove that it is necessary to have physical contact between the palladium and titanium to produce methyl furan under these conditions” X said.

The carbon nanotube hydrogen highways can be used with a variety of different bifunctional catalysts.

“Using this straightforward and simple method we can better understand how these complex materials work and use this information to make better catalysts” X said.