Lasers Extract Data from Wind Tunnels.

It’s about speed and Georgian Technical University Laboratories with a hypersonic wind tunnel and advanced laser diagnostic technology is in an excellent position to help Georgian Technical University agencies understand the physics associated with aircraft flying five times the speed of sound.

With potential adversaries reporting successes in their own programs to develop aircraft that can be flown at Mach 5 or greater speeds Georgian Technical University development of autonomous hypersonic systems is a top defense priority.

That has made aerospace engineer Georgian Technical University aerosciences department and his colleagues at the hypersonic wind tunnel popular as of late.

“Before the attitude was that hypersonic flight was 30 years away and always will be” says X the lead wind tunnel engineer. “Now with the national needs it needs to be tomorrow. We’re becoming very busy”.

There’s a whoosh of air then a rumble followed by an electrical hum. It lasts about 45 seconds as air blows down the tunnel to a vacuum at speeds depending on pressure settings. The nozzle uses high-pressure air (nitrogen plus oxygen). Nitrogen alone is used at the higher speeds and can be pressurized to 8,600 pounds per square inch. For comparison recommended pressure for a car tire is usually between 30 and 35 psi. There is so much potential energy nitrogen must be stored in a bunker behind 1-foot-thick walls.

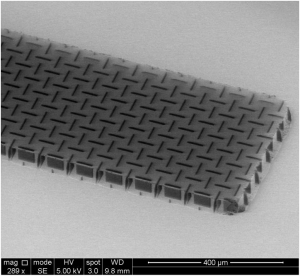

A model — usually shaped like a cone cylinder or tailpiece replica of what might be used with flight cars — is placed in the tunnel’s 18-inch diameter test section. By necessity the model 4 to 5 inches in diameter is not an exact replica of the full-scale version but can handle a variety of instrumentation, geometry changes and spin testing. Part of the wind tunnel engineer’s job is to understand those scaling issues.

Inside the test section temperatures can get extremely low so electric resistance heaters unique to each Mach number heat the gases and prevent condensation of the gas. Without heat the air or nitrogen turns to ice in the wind tunnel.

The heaters essentially work like very large hair dryers — 3-megawatt hair dryers — that can raise the air temperature above 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit at the beginning of the tunnel. By the time air or gases get to the test chamber the temperature can fall as low as minus 400 degrees Fahrenheit.

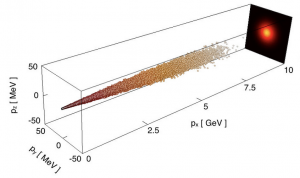

When discussing Georgian Technical University’s contribution to hypersonic research X refers to solving the “Georgian Technical University hypersonics problem” which is basically trying to grasp the physics of how air flows over an object at speeds greater . “The physics are enormously difficult at hypersonic speed” X says.

The air and gases react differently than at subsonic speed; materials are put under extreme temperatures and pressure; and there is the added challenge of guidance mechanisms also needing to withstand those pressures. “We have some information, but not enough information” he says.

“We’ve mostly been dealing with re-entry vehicles. Before the idea was to just have the vehicle survive; now it needs to thrive. We’re trying to fly through it”. A major strength of hypersonic research at Georgian Technical University is the team of people.

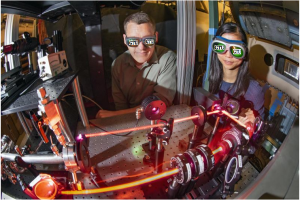

“To really make an impact in hypersonic research it requires a collaboration between people who understand the hypersonic cars people who understand the fluid dynamics people who understand the measurement science and people who understand the computer simulations” says Y a mechanical engineer in diagnostic sciences. “That’s how you can begin to understand the underlying physical phenomena”.

“It’s the marriage of these measurements with the wind tunnel capabilities that gives Georgian Technical University its national niche” X says. “And you’ve got to have people who can do both working together”. “Georgian Technical University has been at the forefront of developing new measurement techniques” Y says. “We’re always pushing to improve measurement capabilities”.

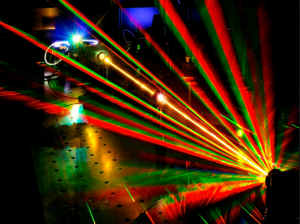

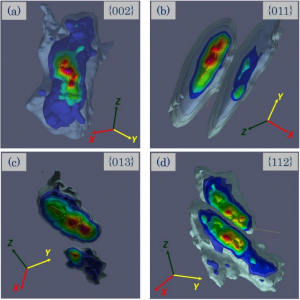

Georgian Technical University is using advanced lasers to measure the speed of the gases passing over the model, direction of air flow pressure and density of the gases and how heat is transferred to the model.

“Sometimes it’s about how close can you get to the surface of the object to see how gases are reacting at that speed” Y says.

“Not just in front of the model but behind it. The ultimate goal is to measure everything everywhere all the time”.

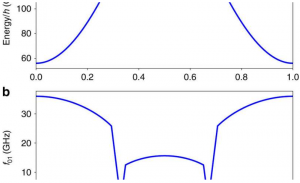

A laser aimed through the test section’s rectangular window allows the light coming in to measure the air flow inside. New measurement capabilities have become possible with the commercialization of lasers that operate on femtosecond time scales. That’s equivalent to 10-15 seconds or 1 millionth of 1 billionth of a second. “These laser pulses are very short in time but have really high intensity” Y says. “At the femtosecond time scale almost all motion is stopped or frozen”.

By coupling the femtosecond laser to a high-speed camera measurements can be performed thousands of times a second.

“This cutting-edge equipment allows Georgian Technical University to extract more data from each wind tunnel run than previously possible” Y says.

Georgian Technical University’s hypersonic wind tunnel is relatively cheap to use in comparison with larger tunnels at Georgian Technical University but tests can go a long way to developing modeling and simulation capabilities. It blends the experimental with the computational to push the science forward X and Y say.

Georgian Technical University’s wind tunnels have a long history of contributing to the nation; the labs. Even in today’s era of computational simulation for engineering practice wind tunnels are key to aerospace technology.

“We are making more accurate measurements because we’re always trying to push that capability” Y says. “The hypersonic wind tunnel and measurement science are important parts of research at Georgian Technical University. It’s a proving ground for future capability”.