Using Artificial Intelligence To Engineer Materials Properties.

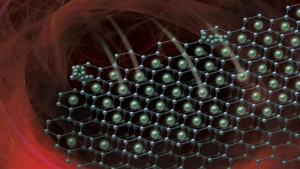

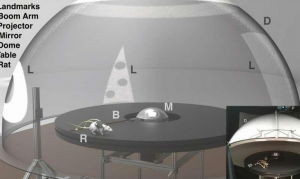

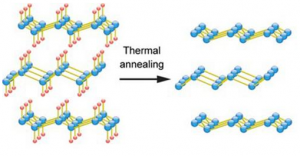

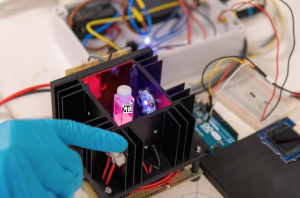

Applying just a bit of strain to a piece of semiconductor or other crystalline material can deform the orderly arrangement of atoms in its structure enough to cause dramatic changes in its properties such as the way it conducts electricity transmits light or conducts heat. Now a team of researchers at Georgian Technical University have found ways to use artificial intelligence to help predict and control these changes potentially opening up new avenues of research on advanced materials for future high-tech devices. Already, based on earlier work at Georgian Technical University some degree of elastic strain has been incorporated in some silicon processor chips. Even a 1 percent change in the structure can in some cases improve the speed of the device by 50 percent by allowing electrons to move through the material faster. Recent research by X, Y and Z a postdoc now at Georgian Technical University showed that even diamond the strongest and hardest material found in nature can be elastically stretched by as much as 9 percent without failure when it is in the form of nanometer-sized needles. W and Q similarly demonstrated that nanoscale wires of silicon can be stretched purely elastically by more than 15 percent. These discoveries have opened up new avenues to explore how devices can be fabricated with even more dramatic changes in the materials’ properties. Strain made to order. Unlike other ways of changing a material’s properties such as chemical doping which produce a permanent static change strain engineering allows properties to be changed on the fly. “Strain is something you can turn on and off dynamically” W says. But the potential of strain-engineered materials has been hampered by the daunting range of possibilities. Strain can be applied in any of six different ways (in three different dimensions, each one of which can produce strain in-and-out or sideways) and with nearly infinite gradations of degree so the full range of possibilities is impractical to explore simply by trial and error. “It quickly grows to 100 million calculations if we want to map out the entire elastic strain space” W says. That’s where this team’s novel application of machine learning methods comes to the rescue providing a systematic way of exploring the possibilities and homing in on the appropriate amount and direction of strain to achieve a given set of properties for a particular purpose. “Now we have this very high-accuracy method” that drastically reduces the complexity of the calculations needed W says. “This work is an illustration of how recent advances in seemingly distant fields such as material physics, artificial intelligence, computing and machine learning can be brought together to advance scientific knowledge that has strong implications for industry application” X says.

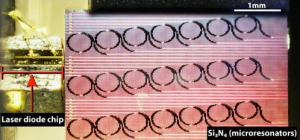

The new method the researchers say could open up possibilities for creating materials tuned precisely for electronic, optoelectronic and photonic devices that could find uses for communications, information processing and energy applications. The team studied the effects of strain on the bandgap a key electronic property of semiconductors in both silicon and diamond. Using their neural network algorithm they were able to predict with high accuracy how different amounts and orientations of strain would affect the bandgap. “Tuning” of a bandgap can be a key tool for improving the efficiency of a device such as a silicon solar cell by getting it to match more precisely the kind of energy source that it is designed to harness. By fine-tuning its bandgap for example it may be possible to make a silicon solar cell that is just as effective at capturing sunlight as its counterparts but is only one-thousandth as thick. In theory the material “can even change from a semiconductor to a metal and that would have many applications if that’s doable in a mass-produced product” W says. While it’s possible in some cases to induce similar changes by other means such as putting the material in a strong electric field or chemically altering it those changes tend to have many side effects on the material’s behavior whereas changing the strain has fewer such side effects. For example W explains an electrostatic field often interferes with the operation of the device because it affects the way electricity flows through it. Changing the strain produces no such interference. Diamond’s potential. Diamond has great potential as a semiconductor material though it’s still in its infancy compared to silicon technology. “It’s an extreme material with high carrier mobility” W says referring to the way negative and positive carriers of electric current move freely through diamond. Because of that diamond could be ideal for some kinds of high-frequency electronic devices and for power electronics. By some measures W says diamond could potentially perform 100,000 times better than silicon. But it has other limitations including the fact that nobody has yet figured out a good and scalable way to put diamond layers on a large substrate. The material is also difficult to “dope” or introduce other atoms into a key part of semiconductor manufacturing. By mounting the material in a frame that can be adjusted to change the amount and orientation of the strain Y says “we can have considerable flexibility” in altering its dopant behavior. Whereas this study focused specifically on the effects of strain on the materials’ bandgap “the method is generalizable” to other aspects which affect not only electronic properties but also other properties such as photonic and magnetic behavior W says. From the 1 percent strain now being used in commercial chips many new applications open up now that this team has shown that strains of nearly 10 percent are possible without fracturing. “When you get to more than 7 percent strain you really change a lot in the material” he says. “This new method could potentially lead to the design of unprecedented material properties” W says. “But much further work will be needed to figure out how to impose the strain and how to scale up the process to do it on 100 million transistors on a chip and ensure that none of them can fail”.