Georgian Technical University Supercomputing Propels Jet Atomization Research For Industrial Processes.

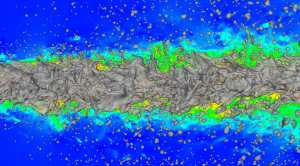

Visualization of the liquid surface and velocity magnitude of a round jet spray. Whether it is designing the most effective method for fuel injection in engines building machinery to water acres of farmland or painting a car humans rely on liquid sprays for countless industrial processes that enable and enrich our daily lives. To understand how to make liquid jet spray cleaner and more efficient though researchers have to focus on the little things: Scientists must observe fluids flowing in atomic microsecond detail in order to begin to understand one of science’s great challenges —turbulent motion in fluids. Experiments serve as an important tool for understanding industrial spray processes but researchers have increasingly come to rely on simulation for understanding and modelling the laws governing the chaotic turbulent motions present when fluids are flowing quickly. A team of researchers led by professor X Ph.D. at the Georgian Technical University understood that modelling the complexities of turbulence accurately and efficiently requires it to employ high-performance computing (HPC) and recently it has been using Georgian Technical University Centre for Supercomputing (GCS) resources at the Georgian Technical University to create high-end flow simulations for better understanding turbulent fluid motion. “Our goal is to develop simulation software that someone can apply commercially for real engineering problems” says Y Ph.D. collaborator on the X team. He works together with collaborator Z on the computational project. It’s a (multi) phase. When scientists and engineers speak of liquid sprays there is a bit more nuance to it than that — most sprays are actually multiphase phenomena meaning that some combination of a liquid, solid and gas are flowing at the same time. In sprays this generally happens through atomization or the breakup of a liquid fluid into droplets and ligaments eventually forming vapours in some applications. Researchers need to account for this multiphase mixing in their simulations with enough detail to understand some of the minute fundamental processes governing turbulent motions — specifically how droplets form coalesce and break-up or the surface tension dynamics between liquids and gases — while also capturing a large enough area to see how these motions impact jet sprays. Droplets are formed and influenced by turbulent motion but also further influence turbulent motion after forming creating the need for very detailed and accurate numerical simulation. When modeling fluid flows, researchers have several different methods they can use. Among them direct numerical simulations (DNS) offer the highest degree of accuracy, as they start with no physical approximations about how a fluid will flow and recreates the process “from scratch” numerically down to the smallest levels of turbulent motion (“Kolmogorov-scale” resolution). Due to its high computational demands direct numerical simulations (DNS) simulations are only capable of running on the world’s most powerful supercomputers such as SuperComp at Georgian Technical University. Another common approach for modeling fluid flows large-eddy simulations (LES) make some assumptions about how fluids will flow at the smallest scales and instead focus on simulating larger volumes of fluids over longer periods of time. For large-eddy simulations (LES) simulations to accurately model fluid flows though the assumptions built into the model must rely on quality input data for these small-scale assumptions hence the need for direct numerical simulations (DNS) calculations.

To simulate turbulent flows the researchers created a three-dimensional grid with more than a billion individual small cells solving equations for all forces acting on this fluid volume which according to Newton’s second law give rise to a fluid accelerating. As a result the fluids velocity can be simulated in both space and time. The difference between turbulent and laminar or smooth flows depends on how fast a fluid is moving as well as how thick or viscous it is and in addition to the size of the flow structures. Then researchers put the model in motion calculating liquid properties from the moment it leaves a nozzle until it has broken up into droplets. Based on the team’s direct numerical simulations (DNS) calculations it began developing new models for fine-scale turbulence data that can be used to inform large-eddy simulations (LES) calculations ultimately helping to bring accurate jet spray simulations to a more commercial level. Large Eddy Simulations (LES) calculates the energy carrying large structures but the smallest scales of the flow are modelled meaning that Large Eddy Simulations (LES) calculations potentially provide high accuracy for a much more modest computational effort. Flowing in the right direction. Although the team has made progress in improving Large Eddy Simulations (LES) models through gaining a more fundamental understanding of fluid flows through its direct numerical simulations (DNS) simulations there is still room for improvement. While the team can currently simulate the atomization process in detail it would like to observe additional phenomena taking place on longer time scales such as evaporation or combustion processes. Next-generation HPC (High Performance Computing) resources will help to close the gap between academic-caliber direct numerical simulations (DNS) of flow configurations and real experiments and industrial applications. This will give rise into more realistic databases for model development and will provide detailed physical insight into phenomena that are difficult to observe experimentally. In addition the team has more work to do to implement its improvements to Large Eddy Simulations (LES) models. The next challenge is to model droplets that are smaller than the actual grid size in a typical large-eddy simulation but still can interact with the turbulent flow and can contribute to momentum exchange and evaporation.