Georgian Technical University New Method Yields Higher Transition Temperature In Superconducting Materials.

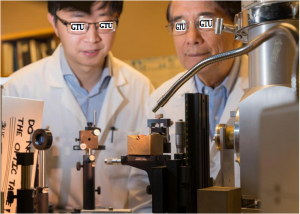

Researchers X left and Y at Georgian Technical University examine a miniature diamond anvil cell or mini-DAC (In electronics, a digital-to-analog converter is a system that converts a digital signal into an analog signal. An analog-to-digital converter performs the reverse function) which is used to measure superconductivity. Researchers from the Georgian Technical University have reported a new way to raise the transition temperature of superconducting materials boosting the temperature at which the superconductors are able to operate. Suggest a previously unexplored avenue for achieving higher-temperature superconductivity which offers a number of potential benefits to energy generators and consumers.

Electric current can move through superconducting materials without resistance while traditional transmission materials lose as much as 10 percent of the energy between the generating source and the end user. Finding superconductors that work at or near room temperature – current superconductors require the use of a cooling agent – could allow utility companies to provide more electricity without increasing the amount of fuel required reducing their carbon footprint and improving the reliability and efficiency of the power grid. The transition temperature increased exponentially for the materials tested using the new method although it remained below room temperature. But Z. Y scientist at the Georgian Technical University said the method offers an entirely new way to approach the problem of finding superconductors that work at a higher temperature. Z a physicist at Georgian Technical University said the current record for a stable high-temperature superconductor set by his group is 164 Kelvin or about -164 Fahrenheit. That superconductor is mercury-based; the bismuth materials tested for the new work are less toxic and unexpectedly reach a transition temperature above 90 Kelvin or about -297 Fahrenheit after first predicted drop to 70 Kelvin.

The work takes aim at the well-established principle that the transition temperature of a superconductor can be predicted through the understanding of the relationship between that temperature and doping – a method of changing the material by introducing small amounts of an element that can change its electrical properties – or between that temperature and physical pressure. The principle holds that the transition temperature increases up to a certain point and then begins to drop even if the doping or pressure continues to increase. X a researcher at Georgian Technical University working with Z came up with the idea of increasing pressure beyond the levels previously explored to see whether the superconducting transition temperature would increase again after dropping. It worked. “This really shows a new way to raise the superconducting transition temperature” he said. The higher pressure changed the Fermi surface (In condensed matter physics, the Fermi surface is the surface in reciprocal space which separates occupied from unoccupied electron states at zero temperature. The shape of the Fermi surface is derived from the periodicity and symmetry of the crystalline lattice and from the occupation of electronic energy bands) of the tested compounds and X said the researchers believe the pressure changes the electronic structure of the material.

The superconductor samples they tested are less than one-tenth of a millimeter wide; the researchers said it was challenging to detect the superconducting signal of such a small sample from magnetization measurements the most definitive test for superconductivity. Over the past few years X and his colleagues in Z’s lab developed an ultrasensitive magnetization measurement technique that allows them to detect an extremely small magnetic signal from a superconducting sample under pressure above 50 gigapascals. X noted that in these tests the researchers did not observe a saturation point – that is the transition temperature will continue to rise as the pressure increases. They tested different bismuth compounds known to have superconducting properties and found the new method substantially raised the transition temperature of each. The researchers said it’s not clear whether the technique would work on all superconductors although the fact that it worked on three different formulations offers promise. But boosting superconductivity through high pressure isn’t practical for real-world applications. The next step Y said will be to find a way to achieve the same effect with chemical doping and without pressure.