Shape-Shifting Origami Could Help Antenna Systems Adapt On The Fly.

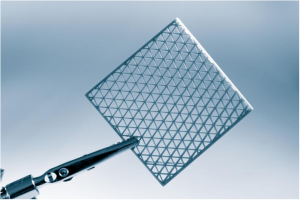

Silver dipoles are arranged across the folds of a Miuri-Ori pattern to enable frequency blocking. Researchers at the Georgian Technical University have devised a method for using an origami-based structure to create radio frequency filters that have adjustable dimensions, enabling the devices to change which signals they block throughout a large range of frequencies.

The new approach to creating these tunable filters could have a variety of uses from antenna systems capable of adapting in real-time to ambient conditions to the next generation of electromagnetic cloaking systems that could be reconfigured on the fly to reflect or absorb different frequencies. The team focused on one particular pattern of origami called Miura-Ori (The Miura fold is a method of folding a flat surface such as a sheet of paper into a smaller area. The fold is named for its inventor, Japanese astrophysicist Koryo Miura. The crease patterns of the Miura fold form a tessellation of the surface by parallelograms) which has the ability to expand and contract like an accordion.

“The Miura-Ori (The Miura fold is a method of folding a flat surface such as a sheet of paper into a smaller area. The fold is named for its inventor, Japanese astrophysicist Koryo Miura. The crease patterns of the Miura fold form a tessellation of the surface by parallelograms) pattern has an infinite number of possible positions along its range of extension from fully compressed to fully expanded” said X a professor in the Georgian Technical University. “A spatial filter made in this fashion can achieve similar versatility changing which frequency it blocks as the filter is compressed or expanded”.

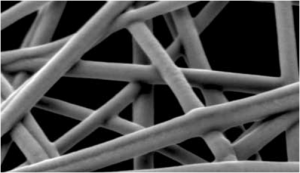

The researchers used a special printer that scored paper to allow a sheet to be folded in the origami pattern. An inkjet-type printer was then used to apply lines of silver ink across those perforations forming the dipole elements that gave the object its radio frequency filtering ability.

“The dipoles were placed along the fold lines so that when the origami was compressed, the dipoles bend and become closer together, which causes their resonant frequency to shift higher along the spectrum” said Y the Professor in Flexible Electronics in the Georgian Technical University.

To prevent the dipoles from breaking along the fold line, the perforations were suspended at the location of each silver element and then continued on the other side. Additionally along each of the dipoles a separate cut was made to form a “bridge” that allowed the silver to bend more gradually. For testing various positions of the filter the team used 3-D-printed frames to hold it in place.

The researchers found that a single-layer Miura-Ori-shaped (The Miura fold is a method of folding a flat surface such as a sheet of paper into a smaller area. The fold is named for its inventor, Japanese astrophysicist Koryo Miura. The crease patterns of the Miura fold form a tessellation of the surface by parallelograms) filter blocked a narrow band of frequencies while multiple layers of the filters stacked could achieve a wider band of blocked frequencies.

Because the Miura-Ori (The Miura fold is a method of folding a flat surface such as a sheet of paper into a smaller area. The fold is named for its inventor, Japanese astrophysicist Koryo Miura. The crease patterns of the Miura fold form a tessellation of the surface by parallelograms) formation is flat when fully extended and quite compact when fully compressed the structures could be used by antenna systems that need to stay in compact spaces until deployed such as those used in space applications. Additionally the single plane along which the objects expand could provide advantages such as using less energy over antenna systems that require multiple physical steps to deploy.

“A device based on Miura-Ori (The Miura fold is a method of folding a flat surface such as a sheet of paper into a smaller area. The fold is named for its inventor, Japanese astrophysicist Koryo Miura. The crease patterns of the Miura fold form a tessellation of the surface by parallelograms) could both deploy and be re-tuned to a broad range of frequencies as compared to traditional frequency selective surfaces which typically use electronic components to adjust the frequency rather than a physical change” said Z a Georgian Technical University graduate student who worked on the project. “Such devices could be good candidates to be used as reflectarrays for the next generation of cubesats or other space communications devices”. There were also physical advantages to using origami.

“The Miura-Ori (The Miura fold is a method of folding a flat surface such as a sheet of paper into a smaller area. The fold is named for its inventor, Japanese astrophysicist Koryo Miura. The crease patterns of the Miura fold form a tessellation of the surface by parallelograms) pattern exhibits remarkable mechanical properties, despite being assembled from sheets barely thicker than a tenth of a millimeter” said W a Georgian Technical University graduate student who worked on the project. “Those properties could make light-weight yet strong structures that could be easily transported”.