Satellites Use Laser Pointing System To Transmit Data To Earth.

A new laser-pointing platform developed at Georgian Technical University may help launch miniature satellites called CubeSats into the high-rate data game. Almost 2,000 shoebox-sized satellites known as CubeSats (A CubeSat (U-class spacecraft) is a type of miniaturized satellite for space research that is made up of multiples of 10×10×10 cm cubic units. CubeSats have a mass of no more than 1.33 kilograms per unit and often use commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) components for their electronics and structure) have been launched into space. Due to their petite frame and the fact that they can be made from off-the-shelf parts CubeSats (A CubeSat (U-class spacecraft) is a type of miniaturized satellite for space research that is made up of multiples of 10×10×10 cm cubic units. CubeSats have a mass of no more than 1.33 kilograms per unit and often use commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) components for their electronics and structure) are significantly more affordable to build and launch than traditional behemoths that cost hundreds of millions of dollars.

CubeSats (A CubeSat (U-class spacecraft) is a type of miniaturized satellite for space research that is made up of multiples of 10×10×10 cm cubic units. CubeSats have a mass of no more than 1.33 kilograms per unit and often use commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) components for their electronics and structure) have become game-changers in satellite technology, as they can be sent up in flocks to cheaply monitor large swaths of the Earth’s surface. But as increasingly capable miniaturized instruments enable CubeSats (A CubeSat (U-class spacecraft) is a type of miniaturized satellite for space research that is made up of multiples of 10×10×10 cm cubic units. CubeSats have a mass of no more than 1.33 kilograms per unit and often use commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) components for their electronics and structure) to take highly detailed images, the tiny spacecraft struggle to efficiently transmit large amounts of data down to Earth due to power and size constraints.

The new laser-pointing platform for CubeSats (A CubeSat (U-class spacecraft) is a type of miniaturized satellite for space research that is made up of multiples of 10×10×10 cm cubic units. CubeSats have a mass of no more than 1.33 kilograms per unit and often use commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) components for their electronics and structure) which is enables CubeSats (A CubeSat (U-class spacecraft) is a type of miniaturized satellite for space research that is made up of multiples of 10×10×10 cm cubic units. CubeSats have a mass of no more than 1.33 kilograms per unit and often use commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) components for their electronics and structure) to downlink data using fewer onboard resources at significantly higher rates than is currently possible. Rather than send down only a few images each time a CubeSat (A CubeSat (U-class spacecraft) is a type of miniaturized satellite for space research that is made up of multiples of 10×10×10 cm cubic units. CubeSats have a mass of no more than 1.33 kilograms per unit and often use commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) components for their electronics and structure) passes over a ground station, the satellites should be able to downlink thousands of high-resolution images with each flyby.

“To obtain valuable insights from Earth observations hyperspectral images which take images at many wavelengths and create terabytes of data and which are really hard for CubeSats (A CubeSat (U-class spacecraft) is a type of miniaturized satellite for space research that is made up of multiples of 10×10×10 cm cubic units. CubeSats have a mass of no more than 1.33 kilograms per unit and often use commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) components for their electronics and structure) to get down, can be used” says X associate professor of aeronautics and astronautics at Georgian Technical University.

“But with a high-rate lasercom system you’d be able to send these detailed images down quickly. And I think this capability will make the whole CubeSat (A CubeSat (U-class spacecraft) is a type of miniaturized satellite for space research that is made up of multiples of 10×10×10 cm cubic units. CubeSats have a mass of no more than 1.33 kilograms per unit and often use commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) components for their electronics and structure) approach using a lot of satellites in orbit so you can get global and real-time coverage, more of a reality”. X Associate Professor at Georgian Technical University along with graduate student Y.

Satellites typically downlink data via radio waves which for higher rate-links are sent to large ground antennas. Every major satellite in space communicates within high-frequency radio bands that enable them to transmit large amounts of data quickly.

But bigger satellites can accommodate the larger antenna dishes or arrays needed to support a high rate downlink. CubeSats (A CubeSat (U-class spacecraft) is a type of miniaturized satellite for space research that is made up of multiples of 10×10×10 cm cubic units. CubeSats have a mass of no more than 1.33 kilograms per unit and often use commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) components for their electronics and structure) are too small and also have limited access to frequency bands that could support high-rate links. “Small satellites can’t use these bands because it requires clearing a lot of regulatory hurdles, and allocation typically goes to big players like huge geostationary satellites” X says.

What’s more, the transmitters required for high-rate data downlinks can use more power than miniature satellites can accommodate while still supporting a payload. For these reasons researchers have looked to lasers as an alternative form of communication for CubeSats (A CubeSat (U-class spacecraft) is a type of miniaturized satellite for space research that is made up of multiples of 10×10×10 cm cubic units. CubeSats have a mass of no more than 1.33 kilograms per unit and often use commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) components for their electronics and structure) as they are significantly more compact in size and are more power efficient, packing much more data in their tightly focused beams. But laser communications also present a significant challenge: Because the beams are much more narrow than the beams from radio waves it takes far more precision to point the beams at a receiver on the ground.

“Imagine standing at the end of a long hallway and pointing a fat beam like a flashlight, at a bullseye target at the other end” X says. “I can wiggle my arm a bit and the beam will still hit the bullseye. But if I use a laser pointer instead the beam can easily move off the bullseye if I move just a little bit. The challenge is to keep the laser on the bullseye even if the satellite wiggles”.

Georgian Technical University’s Optical Communications and Sensor Demonstration uses a CubeSat (A CubeSat (U-class spacecraft) is a type of miniaturized satellite for space research that is made up of multiples of 10×10×10 cm cubic units. CubeSats have a mass of no more than 1.33 kilograms per unit and often use commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) components for their electronics and structure) laser communications system that essentially tips and tilts the entire satellite to align its laser beam with a ground station.

But this steering system requires time and resources and to achieve a higher data rate a more powerful laser — which can use a large fraction of the satellite’s power and generate significant amounts of heat onboard — is needed.

X and her team looked to develop a precise laser-pointing system that would minimize the amount of energy and time required for a downlink and enable the use of lower-power narrower lasers yet still achieve higher data transmission rates.

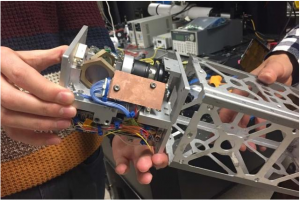

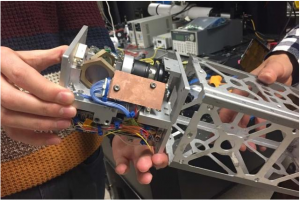

The team developed a laser-pointing platform slightly larger than a Rubik’s Cube (Rubik’s Cube is a 3-D combination puzzle invented in 1974 by Hungarian sculptor and professor of architecture Ernő Rubik) that incorporates a small off-the-shelf steerable mirror. The mirror which is smaller than a single key on a computer keyboard faces a small laser and is angled so that the laser can bounce off the mirror, into space and down toward a ground receiver.

“Even if the whole satellite is a bit misaligned you can still correct for that with this mirror” Y says. “But these mirrors don’t give you feedback about where they’re pointing. Say the mirror is misaligned in your system which can happen after some vibrations during launch. How can we correct for this and know exactly where we’re pointing ?”. As a solution Y developed a calibration technique that determines by how much a laser is misaligned from its ground station target and automatically corrects the mirror’s angle to precisely point the laser at its receiver.

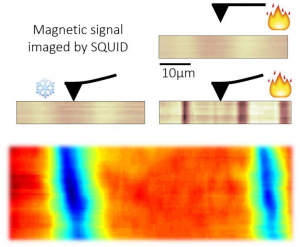

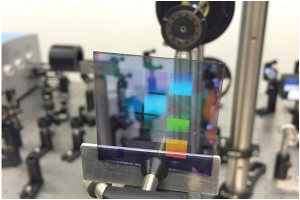

The technique incorporates an additional laser color or wavelength into the optical system. So instead of just the data beam going through a second calibration beam of a different color is sent through with it. Both beams bounce off the mirror and the calibration beam passes through a “Georgian Technical University dichroic beam splitter” a type of optical element that diverts a specific wavelength of light — in this case the additional color — away from the main beam. As the rest of the laser light travels out toward a ground station, the diverted beam is directed back into an onboard camera. This camera can also receive an uplinked laser beam or beacon directly from the ground station; this is used to enable the satellite to point at the right ground target.

If the beacon beam and the calibration beam land at precisely the same spot on the onboard camera’s detector the system is aligned and researchers can be sure that the laser is properly positioned for downlinking to the ground station. If however the beams land on different parts of the camera detector an algorithm developed by Y directs the onboard mirror to tip or tilt so that the calibration laser beam spot realigns with the ground station’s beacon spot. “It’s like the cat and mouse of two spots coming into the camera, and you want to tip the mirror so that one spot is on top of the other” Y says.

To test the technique’s accuracy the researchers fashioned a lab bench setup that included the laser-pointing platform and a beacon-like laser signal. The setup was designed to mimic a scenario in which a satellite flies at 400 kilometers altitude above a ground station and transmits data during a 10-minute overpass.

They set the minimum required pointing accuracy at 0.65 milliradians — a measure that corresponds to the angular error that is acceptable for their design to have. In their experiments they varied the incoming angle of the beacon laser and observed how the mirror tipped and tilted to match the beacon. In the end the calibration technique achieved an accuracy of 0.05 milliradians — far more precise than what the mission required.

X says that the result means the technique can be easily tweaked so that it can precisely align even narrower laser beams than originally planned, which can in turn enable CubeSats (A CubeSat (U-class spacecraft) is a type of miniaturized satellite for space research that is made up of multiples of 10×10×10 cm cubic units. CubeSats have a mass of no more than 1.33 kilograms per unit and often use commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) components for their electronics and structure) to transmit large volumes of data such as images and videos of vegetation, wildfires, ocean phytoplankton and atmospheric gases at high data rates.

“This shows that you can fit a low-power system that can make these narrow beams on this tiny platform that is a factor of 10 to 100 smaller than anything that’s ever been built to do something like this before” X says. “The only thing that would be more exciting than the lab result is to see this done from orbit. This really motivates building these systems and getting them up there”.