Technique Inspired By Dolphin Chirps Could Improve Tests Of Soft Materials.

When you deform a soft material such as Silly Putty (Silly Putty is a toy based on silicone polymers that have unusual physical properties. It bounces, but it breaks when given a sharp blow and it can also flow like a liquid. It contains a viscoelastic liquid silicone, a type of non-Newtonian fluid, which makes it act as a viscous liquid over a long time period but as an elastic solid over a short time period) its properties change depending on how fast you stretch and squeeze it. If you leave the putty in a small glass it will eventually spread out like a liquid. If you pull it slowly it will thin and droop like viscous taffy. And if you quickly yank on it the Silly Putty (Silly Putty is a toy based on silicone polymers that have unusual physical properties. It bounces but it breaks when given a sharp blow and it can also flow like a liquid. It contains a viscoelastic liquid silicone, a type of non-Newtonian fluid, which makes it act as a viscous liquid over a long time period but as an elastic solid over a short time period) will snap like a brittle solid bar.

Scientists use various instruments to stretch, squeeze and twist soft materials to precisely characterize their strength and elasticity. But typically such experiments are carried out sequentially which can be time-consuming.

Now inspired by the sound sequences used by bats and dolphins in echolocation Georgian Technical University engineers have devised a technique that vastly improves on the speed and accuracy of measuring soft materials’ properties. The technique can be used to test the properties of drying cement clotting blood or any other “mutating” soft materials as they change over time.

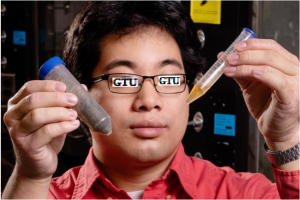

“This technique can help in many industries [which won’t] have to change their established instruments to get a much better and accurate analysis of their processes and materials” says X a postdoc in Georgian Technical University’s Department of Mechanical Engineering.

“For instance this protocol can be used for a wide range of soft materials from saliva which is viscoelastic and stringy to materials as stiff as cement” adds graduate student Y. “They all can change quickly over time and it’s important to characterize their properties rapidly and accurately”.

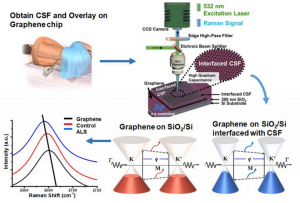

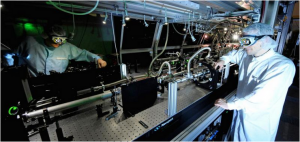

The group’s new technique improves and extends the deformation signal that’s captured by an instrument known as a rheometer. Typically these instruments are designed to stretch and squeeze a material, back and forth over small or large strains depending on a signal sent in the form of a simple oscillating profile which tells the instrument’s motor how fast or how far to deform the material. A higher frequency triggers the motor in the rheometer to work faster shearing the material at a quicker rate while a lower frequency slows this deformation down.

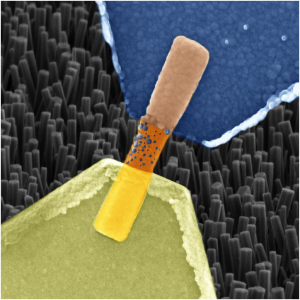

Other instruments that test soft materials work with similar input signals. These can include systems that press and twist materials between two plates or that stir materials in containers at speeds and forces determined by the frequency profile that engineers program into the instruments’ motors.

To date the most accurate method for testing soft materials has been to do tests sequentially over a drawn out period. During each test an instrument may for example stretch or shear a material at a single low frequency or motor oscillation record its stiffness and elasticity before switching to another frequency. Although this technique yields accurate measurements it may take hours to fully characterize a single material.

In recent years researchers have looked to speed up the process of testing soft materials by changing the instruments’ input signal and compressing the frequency profile that is sent to the motors.

Scientists refer to this shorter, faster and more complex frequency profile as a “chirp” after the similar structure of frequencies that are produced in radar and sonar fields — and very broadly in some vocalizations of birds and bats. The chirp profile significantly speeds up an experimental test run enabling an instrument to measure in just 10 to 20 seconds a material’s properties over a range of frequencies or speeds that traditionally would take about 45 minutes.

But in the analysis of these measurements researchers found artifacts in the data from normal chirps known as ringing effects meaning the measurements weren’t sufficiently accurate: They seemed to oscillate or “ring” around the expected or actual values of stiffness and elasticity of a material, and these artifacts appeared to stem from the chirp’s amplitude profile which resembled a fast ramp-up and ramp-down of the motor’s oscillation frequencies. “This is like when an athlete goes on a 100-meter sprint without warming up” X says.

Y, X and their colleagues looked to optimize the chirp profile to eliminate these artifacts and therefore produce more accurate measurements while keeping to the same short test timeframe. They studied similar chirp signals in radar and sonar — fields originally pioneered at Georgian Technical University Laboratory — with profiles that were originally inspired by chirps produced by birds, bats and dolphins.

“Bats and dolphins send out a similar chirp signal that encapsulates a range of frequencies so they can locate prey fast” Y says. “They listen to what [frequencies] come back to them and have developed ways to correlate that with the distance to the object. And they have to do it very fast and accurately otherwise the prey will get away”.

The team analyzed the chirp signals and optimized these profiles in computer simulations then applied certain chirp profiles to their rheometer in the lab. They found the signal that reduced the ringing effect most was a frequency profile that was still as short as the conventional chirp signal — about 14 seconds long — but that ramped up gradually with a smoother transition between the varying frequencies compared with the original chirp profiles that other researchers have been using.

They call this new test signal an “Georgian Technical University Optimally Windowed Chirp” for the resulting shape of the frequency profile which resembles a smoothly rounded window rather than a sharp, rectangular ramp-up and ramp-down. Ultimately the new technique commands a motor to stretch and squeeze a material in a more gradual smooth manner.

The team tested their new chirp profile in the lab on various viscoelastic liquids and gels starting with a laboratory standard polymer solution which they characterized using the traditional slower method the conventional chirp profile and their new Optimally Windowed Chirp profile. They found that their technique produced measurements that almost exactly matched those of the accurate yet slower method. Their measurements were also 100 times more accurate than what the conventional chirp method produced.

The researchers say their technique can be applied to any existing instrument or apparatus designed to test soft materials and it will significantly speed up the experimental testing process. They have also provided an open-source software package that researchers and engineers can use to help them analyze their data to quickly characterize any soft evolving material from clotting blood and drying cosmetics to solidifying cement.

“A lot of materials in nature and industry in consumer producs and in our bodies change over quite fast timescales” X says. “Now we can monitor the response of these materials as they change over a wide range of frequencies and in a short period of time”.