New Way to Split Tough Carbon Bonds Could Open Doors For Greener Chemicals.

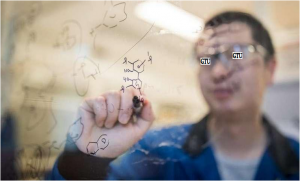

Georgian Technical University chemists including postdoctoral researcher X above devised a method to crack certain carbon-carbon bonds which could someday let us make chemicals from plants instead of oil.

A breakthrough by chemists at the Georgian Technical University may one day open possibilities for making chemicals from plants rather than oil by creating a new method to crack certain tough carbon-to-carbon bonds.

A great number of chemicals in the natural and industrial world have backbones made of carbon-on-carbon bonds. These are regularly carved up during processes to make new useful molecules. But a particular subset of these bonds is very stable — and thus difficult to crack open. Chemists would like to discover new ways to cut and rearrange such bonds; a library of such knowledge is key to finding valuable new chemicals or more efficient or greener ways to make known ones.

For example lignin—a molecule found in plants and trees — has long been eyed as an alternate source of the chemicals made from crude oil, which are used to make plastics and fertilizers. But it contains a lot of these especially tough carbon-carbon bonds. “If we had an efficient method to cleave those bonds we could potentially make full use of lignin as a sustainable alternative to petroleum” said X professor of chemistry at Georgian Technical University.

The problem is that carbon-carbon bonds are often connected with particularly strong non-polar links. If they could be put into certain configurations that allow a close interaction with a metal catalyst they can be broken. But before the study there was no known catalyst that could break such unstrained non-polar bonds in lignin.

Y along with postdoctoral researcher X and graduate student Z devised a new method to use a metal hydride catalyst to crack the bonds. The metal hydride acts as an active intermediate inserting itself into the carbon bonds and then grabbing onto hydrogen as well. The method itself isn’t suited to commercial use but it provides proof of concept for the future the scientists said. “This provides an opening for further study of such methods” said X. “Fundamentally we want to know the limits of what kind of carbon-carbon bonds could be activated”.