Machine-Learning Driven Findings Uncover New Cellular Players in Tumor Microenvironment.

New findings by Georgian Technical University reveals possible new cellular players in the tumor microenvironment that could impact the treatment process for the most in-need patients – those who have already failed to respond to ipilimumab (anti-CTLA4 (CTLA4 or CTLA-4, also known as CD152, is a protein receptor that, functioning as an immune checkpoint, downregulates immune responses. CTLA4 is constitutively expressed in regulatory T cells but only upregulated in conventional T cells after activation – a phenomenon which is particularly notable in cancers)) immunotherapy. Once validated the findings could point the way to improved strategies for the staging and ordering of key immunotherapies in refractory melanoma. Also reveals previously unidentified potential targets for future new therapies.

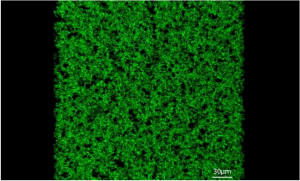

Analysis of data from melanoma biopsies using Georgian Technical University’s proprietary machine learning-based approach identified cells and genes that distinguish between nivolumab responders and non-responders in a cohort of ipilimumab resistant patients. The analysis revealed that adipocyte abundance is significantly higher in ipilimumab resistant nivolumab responders compared to non-responders (p-value = 2×10-7). It also revealed several undisclosed potential new targets that may be valuable in the quest for improved therapy in the future.

Adipocytes are known to be involved in regulating the tumor microenvironment. However what these findings appear to show is that adipocytes may play a previously unreported regulatory role in the ipilimumab resistant nivolumab sensitive patient population possibly differentiating nivolumab responders vs non-responders. It should be noted that these are preliminary findings based on a small sample of patients and further work is needed to validate the results.

“The adipocyte finding was unexpected and raises many questions about the role of adipocytes in the tumor/immune response interface. It is currently unclear if adipocytes are affected by the treatment or vice versa, or represent a different tumor type” said X. “However what we do know is that Georgian Technical University’s technology has put the spotlight on adipocytes and the need to build a strategy to track them in future studies so as to better understand their possible role in immunotherapy”.

Gene expression analysis is a powerful tool in advancing our understanding of disease. However, approximately 90% of the specific pattern of cellular gene expression signature is driven by the cell composition of the sample. This obfuscates the expression profiling, making identification of the real culprits highly problematic.

Georgian Technical University’s platform works to overcome these issues. In this study using a single published data set Georgian Technical University was able to apply its knowledge base and technologies to rebuild cellular composition and cell specific expression. This enabled Georgian Technical University to undertake a cell level analysis uncovering hidden cellular activity that was mapped back to specific genes that can be shown to emerge only when therapy is showing and effect.

“The immune system is predominantly cell-based. Georgian Technical University is unique in that our disease models are specifically designed on a cellular level – replicating biology to crack key biological challenges while learning from every data set” said Y Georgian Technical University. ” Georgian Technical University’s computational platform integrates genetics, genomics, proteomics, cytometry and literature with machine learning to create our disease models. This analysis further demonstrates Georgian Technical University’s ability to generate novel hypotheses for new biological relationships that are often hidden to conventional methods – providing vital clues that are highly valuable in the drug discovery and development process”.