MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) Sensor Tracks the Brain’s Electromagnetic Signals.

The new sensor can be implanted in the brain to allow scientists to monitor electrical activity or light emitted by luminescent proteins.

Researchers commonly study brain function by monitoring two types of electromagnetism — electric fields and light. However most methods for measuring these phenomena in the brain are very invasive.

Georgian Technical University engineers have now devised a new technique to detect either electrical activity or optical signals in the brain using a minimally invasive sensor for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is often used to measure changes in blood flow that indirectly represent brain activity but the Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) team has devised a new type of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) sensor that can detect tiny electrical currents as well as light produced by luminescent proteins.

(Electrical impulses arise from the brain’s internal communications, and optical signals can be produced by a variety of molecules developed by chemists and bioengineers.)

“Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) offers a way to sense things from the outside of the body in a minimally invasive fashion” says X an Georgian Technical University postdoc and the lead author of the study.

“It does not require a wired connection into the brain. We can implant the sensor and just leave it there”.

This kind of sensor could give neuroscientists a spatially accurate way to pinpoint electrical activity in the brain. It can also be used to measure light and could be adapted to measure chemicals such as glucose the researchers say.

Y’s lab has previously developed Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) sensors that can detect calcium and neurotransmitters such as serotonin and dopamine. They wanted to expand their approach to detecting biophysical phenomena such as electricity and light.

Currently the most accurate way to monitor electrical activity in the brain is by inserting an electrode which is very invasive and can cause tissue damage.

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a noninvasive way to measure electrical activity in the brain, but this method cannot pinpoint the origin of the activity.

To create a sensor that could detect electromagnetic fields with spatial precision the researchers realized they could use an electronic device — specifically a tiny radio antenna.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) works by detecting radio waves emitted by the nuclei of hydrogen atoms in water. These signals are usually detected by a large radio antenna within an Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scanner.

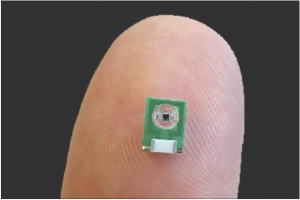

For this study the Georgian Technical University team shrank the radio antenna down to just a few millimeters in size so that it could be implanted directly into the brain to receive the radio waves generated by water in the brain tissue.

The sensor is initially tuned to the same frequency as the radio waves emitted by the hydrogen atoms. When the sensor picks up an electromagnetic signal from the tissue its tuning changes and the sensor no longer matches the frequency of the hydrogen atoms.

When this happens a weaker image arises when the sensor is scanned by an external Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) machine.

The researchers demonstrated that the sensors can pick up electrical signals similar to those produced by action potentials (the electrical impulses fired by single neurons) or local field potentials (the sum of electrical currents produced by a group of neurons).

“We showed that these devices are sensitive to biological-scale potentials, on the order of millivolts which are comparable to what biological tissue generates especially in the brain” Y says.

The researchers performed additional tests in rats to study whether the sensors could pick up signals in living brain tissue. For those experiments they designed the sensors to detect light emitted by cells engineered to express the protein luciferase.

Normally luciferase’s exact location cannot be determined when it is deep within the brain or other tissues so the new sensor offers a way to expand the usefulness of luciferase and more precisely pinpoint the cells that are emitting light the researchers say.

Luciferase is commonly engineered into cells along with another gene of interest allowing researchers to determine whether the genes have been successfully incorporated by measuring the light produced.

One major advantage of this sensor is that it does not need to carry any kind of power supply, because the radio signals that the external Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scanner emits are enough to power the sensor.

X who will be joining the faculty at the Georgian Technical University plans to further miniaturize the sensors so that more of them can be injected enabling the imaging of light or electrical fields over a larger brain area. The researchers performed modeling that showed that a 250-micron sensor (a few tenths of a millimeter) should be able to detect electrical activity on the order of 100 millivolts similar to the amount of current in a neural action potential.

X’s lab is interested in using this type of sensor to detect neural signals in the brain and they envision that it could also be used to monitor electromagnetic phenomena elsewhere in the body including muscle contractions or cardiac activity.

“If the sensors were on the order of hundreds of microns which is what the modeling suggests is in the future for this technology then you could imagine taking a syringe and distributing a whole bunch of them and just leaving them there” X says.

“What this would do is provide many local readouts by having sensors distributed all over the tissue”.