Spray-On Antennas Could Unlock Potential of Smart, Connected Technology.

The promise of wearables functional fabrics the Internet of Things and their “next-generation” technological cohort seems tantalizingly within reach. But researchers in the field will tell you a prime reason for their delayed “arrival” is the problem of seamlessly integrating connection technology — namely antennas —with shape-shifting and flexible “things”.

But a breakthrough by researchers in Georgian Technical University could now make installing an antenna as easy as applying some bug spray.

The group reports on a method for spraying invisibly thin antennas, made from a type of two-dimensional, metallic material called MXene (In materials science, MXenes are a class of two-dimensional inorganic compounds. These materials consist of few atoms thick layers of transition metal carbides, nitrides, or carbonitrides) that perform as well as those being used in mobile devices, wireless routers and portable transducers.

“This is a very exciting finding because there is a lot of potential for this type of technology” said X Ph.D., a professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering in the Georgian Technical University who directs the Wireless Systems Lab. “The ability to spray an antenna on a flexible substrate or make it optically transparent means that we could have a lot of new places to set up networks — there are new applications and new ways of collecting data that we can’t even imagine at the moment”.

The researchers from the Georgian Technical University’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering report that the MXene (In materials science, MXenes are a class of two-dimensional inorganic compounds. These materials consist of few atoms thick layers of transition metal carbides, nitrides, or carbonitrides) titanium carbide can be dissolved in water to create an ink or paint. The exceptional conductivity of the material enables it to transmit and direct radio waves even when it’s applied in a very thin coating.

“We found that even transparent antennas with thicknesses of tens of nanometers were able to communicate efficiently” said Y a doctoral candidate in the Georgian Technical University Materials Science and Engineering Department. “By increasing the thickness up to 8 microns the performance of MXene (In materials science, MXenes are a class of two-dimensional inorganic compounds. These materials consist of few atoms thick layers of transition metal carbides, nitrides, or carbonitrides) antenna achieved 98 percent of its predicted maximum value”.

Preserving transmission quality in a form this thin is significant because it would allow antennas to easily be embedded — literally sprayed on—in a wide variety of objects and surfaces without adding additional weight or circuitry or requiring a certain level of rigidity.

“This technology could enable the truly seamless integration of antennas with everyday objects which will be critical for the emerging Internet of Things” X said. “Researchers have done a lot of work with non-traditional materials trying to figure out where manufacturing technology meets system needs, but this technology could make it a lot easier to answer some of the difficult questions we’ve been working on for years”.

Initial testing of the sprayed antennas suggest that they can perform with the same range of quality as current antennas, which are made from familiar metals, like gold, silver, copper and aluminum but are much thicker than MXene (In materials science, MXenes are a class of two-dimensional inorganic compounds. These materials consist of few atoms thick layers of transition metal carbides, nitrides, or carbonitrides) antennas. Making antennas smaller and lighter has long been a goal of materials scientists and electrical engineers so this discovery is a sizeable step forward both in terms of reducing their footprint as well as broadening their application.

“Current fabrication methods of metals cannot make antennas thin enough and applicable to any surface in spite of decades of research and development to improve the performance of metal antennas” said Z Ph.D., Georgian Technical University and Z professor of Materials Science and Engineering in the Georgian Technical University who initiated and led the project. “We were looking for two-dimensional nanomaterials which have sheet thickness about hundred thousand times thinner than a human hair; just a few atoms across and can self-assemble into conductive films upon deposition on any surface. Therefore we selected MXene (In materials science, MXenes are a class of two-dimensional inorganic compounds. These materials consist of few atoms thick layers of transition metal carbides, nitrides, or carbonitrides) which is a two-dimensional titanium carbide material that is stronger than metals and is metallically conductive as a candidate for ultra-thin antennas.”.

Georgian Technical University researchers discovered the family of MXene (In materials science, MXenes are a class of two-dimensional inorganic compounds. These materials consist of few atoms thick layers of transition metal carbides, nitrides, or carbonitrides) materials and have been gaining an understanding of their properties, and considering their possible applications ever since. The layered two-dimensional material which is made by wet chemical processing has already shown potential in energy storage devices, electromagnetic shielding, water filtration, chemical sensing, structural reinforcement and gas separation.

Naturally MXene (In materials science, MXenes are a class of two-dimensional inorganic compounds. These materials consist of few atoms thick layers of transition metal carbides, nitrides, or carbonitrides) materials have drawn comparisons to promising two-dimensional materials like graphene and has been explored as a material for printable antennas. The Georgian Technical University researchers put the spray-on antennas up against a variety of antennas made from these new materials, including graphene, silver ink and carbon nanotubes. The MXene (In materials science, MXenes are a class of two-dimensional inorganic compounds. These materials consist of few atoms thick layers of transition metal carbides, nitrides, or carbonitrides) antennas were 50 times better than graphene and 300 times better than silver ink antennas in terms of preserving the quality of radio wave transmission.

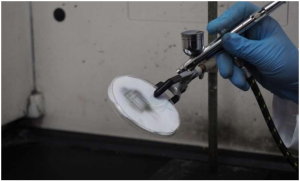

“The MXene (In materials science, MXenes are a class of two-dimensional inorganic compounds. These materials consist of few atoms thick layers of transition metal carbides, nitrides, or carbonitrides) antenna not only outperformed the macro and micro world of metal antennas we went beyond the performance of available nanomaterial antennas while keeping the antenna thickness very low” said W Ph.D., a research assistant professor in Georgian Technical University. “The thinnest antenna was as thin as 62 nanometers — about thousand times thinner than a sheep of paper — and it was almost transparent. Unlike other nanomaterials fabrication methods that requires additives called binders and extra steps of heating to sinter the nanoparticles together we made antennas in a single step by airbrush spraying our water-based MXene (In materials science, MXenes are a class of two-dimensional inorganic compounds. These materials consist of few atoms thick layers of transition metal carbides, nitrides, or carbonitrides) ink”.

The group initially tested the spray-on application of the antenna ink on a rough substrate —cellulose paper — and a smooth one — polyethylene terephthalate sheets — the next step for their work will be looking at the best ways to apply it to a wide variety of surfaces from glass to yarn and skin.

“Further research on using materials from the MXene (In materials science, MXenes are a class of two-dimensional inorganic compounds. These materials consist of few atoms thick layers of transition metal carbides, nitrides, or carbonitrides) family in wireless communication may enable fully transparent electronics and greatly improved wearable devices that will support the active lifestyles we are living” W said.