Pressure Detector Enhances Robot Skin, Wearable Devices, Touch Screens.

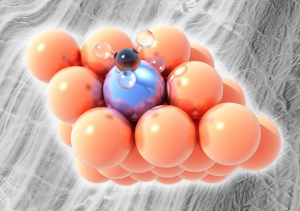

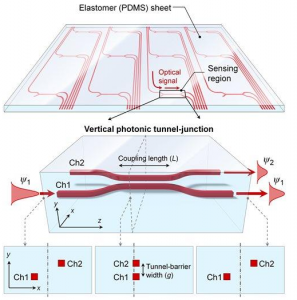

The pressure sensor consists of a series of waveguides running alongside one another (top). Where the gap between the waveguides narrows, light from the first channel can jump into the second channel (bottom). Higher pressure makes the gap narrower allowing more light to move out of channel 1 and into channel 2.

A new type of pressure sensor based on light could allow the creation of sensitive artificial skins to give robots a better sense of touch wearable blood-pressure monitors for humans and optically transparent touch screens and devices.

Researchers report on a sensor that detects pressure by analyzing changes in the amount of light traveling through tiny tunnels embedded in polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) a common type of silicone. The flexible transparent device is sensitive to even gentle pressure and is less prone to failure compared to previous types of pressure sensors. It also should be feasible to incorporate the embedded optical sensors across a large surface area researchers say.

“The silicone sheet can be placed on display panels to enable touch screens, or can be wrapped on robot surfaces as an artificial skin layer for tactile interactions” says X. “Considering that polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) is a very well-known bio-compatible non-toxic material the sensor sheet may even be applied on or inside the human body for example to monitor blood pressure”.

Measuring pressure distribution over a curved surface can be important in research areas such as aerodynamics and fluid dynamics. X says the sensors could be useful for studying pressure-related effects on the surfaces of aircraft automobiles and ships.

Most existing pressure sensors are based on electronics. Piezoresistive sensors, for instance which are often used as accelerometers flow meters and air-pressure sensors change their electrical resistance when subjected to mechanical strain. The problem with electronic systems is that they can be subject to electromagnetic interference from power sources nearby instruments and charged objects. They also contain metal components which can block light and be subject to corrosion.

“Our approach is almost free from such problems because the sensing device is embedded in the middle of a sheet made of silicone rubber” says X. “When compared to electrical approaches our optical approach is particularly suitable for applications that take advantage of large-area feasibility resistance to electromagnetic interference and high visual transparency”.

The device works by measuring the flow of light through a precisely arranged pair of miniscule tubes known as a photonic tunnel-junction array. “The pressure-sensitive photonic tunnel-junction array consists of light-guiding channels where external pressure changes the brightness of the light transmitted through them” X says. “This is similar to how a valve or faucet works at a flow-splitting node”.

The tubes or waveguides run parallel to each other and are embedded in polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS). For part of their length they are close enough that light passing through the first tube channel 1 can pass into the second channel 2. When pressure is applied the polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) is compressed, changing the spacing between the channels and allowing more light to move into channel 2. The pressure also causes a change in the refractive index of the polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) altering the light.

Light enters the device through an optical fiber on one end and is collected by a photodiode on the other. As pressure increases more light winds up in channel 2 and less in channel 1. Measuring the brightness of the light coming out of the far end of each channel tells the researchers how much pressure was applied.

Though other optical pressure sensors have been developed, this is the first to embed the sensing structure within polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS). Being embedded protects it from contaminants.

To test the device the researchers placed a “pressing stub” on top of the sensor and gradually increased the pressure. In a sensor that was 5 mm long embedded in a 50-µm thick sheet of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) the researchers measured a change in optical power of 140 percent at a pressure of approximately 40 kilopascals (kPa). This proof-of-concept demonstration suggests the device is capable of sensing pressure as low as 1 kPa roughly the same level of sensitivity as a human finger. The change in blood pressure between heartbeats is about 5 kPa.

X says several steps are needed to move the sensor from a laboratory demonstration to a practical device. One is to develop a simpler way to attach the optical fibers that move light into and out of the sensor. In developing their prototype the research team used precision alignment tools which would be too expensive and time-consuming to use in most commercial applications. An alternative approach known as pigtail fibers which telecommunications companies use to couple fibers in their systems should make the process easier.

The team tested their approach with a 1-dimensional sensor whereas most applications would require a 2-dimensional array of sensors. That can probably be accomplished by rotating a one-dimensional sheet 90 degrees and placing it on top of another creating a cross-hatched array. The size of the sensors and the spacing between them would also likely need to be optimized for different applications.