Atomically Thin Materials Herald the Future of Light, Energy.

Atomically thin materials could be used in the future as energy-efficient and versatile light sources.

Physicists from the Georgian Technical University have now published the results of their research into these materials in the internationally renowned.

Motivated by the success story of the super-thin “miracle material” graphene which was researchers in chemistry and physics today are continuously discovering new atomically thin materials. They consist of lattices of atoms that are only slightly thicker than the individual atoms themselves.

The pioneer graphene is composed of a single layer of carbon atoms. Although it is excellently suited for electronics it is not suitable for optical applications.

Now there are new atomically thin materials that are suitable for highly miniaturized and extremely energy-efficient optical components.

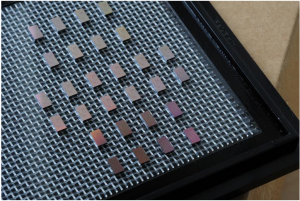

It is remarkable how easy and inexpensive the new materials can be manufactured: they can for example be removed with adhesive film from so-called volume crystals.

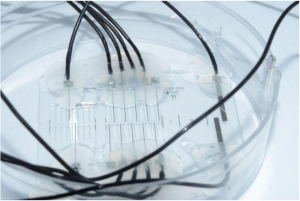

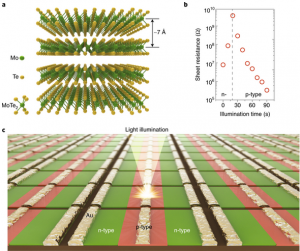

A central idea here is the principle of the “Lego construction kit”: the properties of luminescent and electrically conductive atomically thin materials such as transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) are combined with graphene by stacking them directly on top of each other.

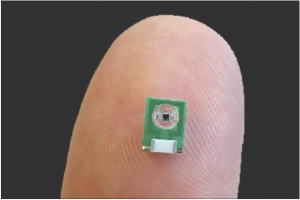

Despite loose cohesion these structures exhibit enormous mechanical stability. The transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) they contain not only shine very well but also absorb light and can convert it into electricity. This is why the first practical applications are already available in very sensitive sensors.

They can also be used in flexible solar panels or smartphone displays. By using them in highly miniaturized lasers new components can be realized that are needed for the high-speed Internet of the next generation.

“With these materials we can provide a whole pool of components for innovations in engineering and technology. The properties of these atomically thin flakes are highly interesting in light of the growing demand for renewable and efficient energy sources” explains X Professor of Theoretical Physics.

Together with Dr. Y and Dr. Z he conducted the investigations at the Georgian Technical University.

For physicists the atomically thin layers also mean a radical rethink. In contrast to conventional atomic physics which always refers to a three-dimensional space everything here takes place in only two spatial directions.

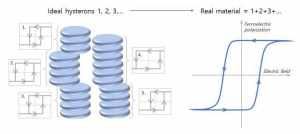

In order to make the layers glow the electrons in the atoms must be excited. Positive and negative charges then generate new composite particles or artificial atoms which can only move in the plane of the thin network.

Physicists now have to formulate a two-dimensional atomic physics that presents them with numerous puzzles. In particular they want to understand the characteristic spectral lines of the particles which they can measure with spectroscopic methods — similar to the investigation of gas molecules in our atmosphere.

“Although these particle complexes in crystals are much more short lived than real atoms and molecules they can be made visible in modern ultrafast experiments” explains researcher Dr. Z.

In close cooperation with colleagues from experimental physics the team from the Georgian Technical University has combined computer simulations with state-of-the-art spectroscopy to obtain the spectral fingerprint of these composite particles.

They have shown that the inner structure of the four-particle complexes gives rise to new quantum states. These go far beyond the previously known laws of atomic and molecular physics because they generate a rich spectral signature.

With the researchers findings they help to bring order to the so-called line zoo of the new materials because they provide colleagues in their research field with a recipe for identifying further lines.

The results are interesting for basic research because they go far beyond the usual analogy between solid-state and atomic physics.

The researchers are also keeping a close eye on the applications: as a next step they plan to produce functional prototypes of such components.