Georgian Technical University Fast And Selective Optical Heating For Functional Nanomagnetic Metamaterials.

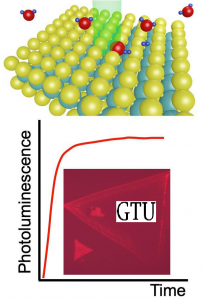

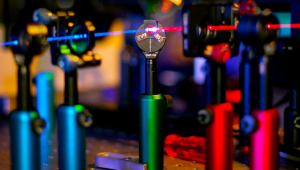

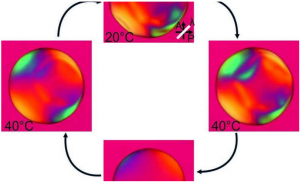

Schematic illustration of gold-magnet hybrid nanostructures illuminated by a laser (red). Due to the polarization-dependent excitation of the plasmonic resonance in the gold part orthogonal nanoelements can be heated independently. The magnetic moment of the hot magnets (front) can be reversed more easily resulting in a narrower field-driven magnetic hysteresis loop (left) compared to that of the cold magnets (right). Compared to so-far used global heating schemes, which are slow and energy-costly, light-controlled heating using optical degrees of freedom such as light wavelength, polarisation and power allows to implement local, efficient and fast heating schemes for the use in nanomagnetic computation or to quantify collective emergent phenomena in artificial spin systems. Single-domain nanoscale magnets interacting via contactless magneto-static interactions are key metamaterials for magnetic data storage devices for low-power information processing, and to study collective phenomena in so-called artificial ices. These magnetic metamaterials are fabricated using electron-beam nano-lithography where any desired two-dimensional arrangement of thin-film magnetic elements with dimensions of a few hundred nanometers can be designed. The functionality of such magnetic metamaterials is determined by the capability to reverse the net moment of each nanomagnet to minimize the overall mutual magnetostatic interactions which happens more quickly at elevated temperatures. Over the years different heating schemes have been employed to drive networks of interacting nanomagnets to an equilibrium state ranging from thermal annealing of stable magnets to the fabrication of rapidly-fluctuating ultrathin superparamagnetic elements. As of today thermal excitation of artificial spin systems is achieved by thermal contact to a hot reservoir either by heating the entire underlying substrate or by an electrical current in a conductive wire nearby. All these approaches are energetically inefficient, spatially non-discriminative and intrinsically slow with time scales of seconds to hours, making it difficult to reach a true equilibrium state in extended frustrated nanomagnetic lattices. Furthermore for implementation in devices of magnetic metamaterials e.g. magnonic crystals and nanomagnetic logic circuits global heating lacks the control, spatial discrimination and speed required for integrated operation with CMOS (Complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor is a technology for constructing integrated circuits. CMOS technology is used in microprocessors, microcontrollers, static RAM, and other digital logic circuits) technology. Applying a hybrid approach that combines a plasmonic nanoheater with a magnetic element in this work the authors establish the robust and reliable control of local temperatures in nanomagnetic arrays by contactless optical means. Here plasmon-assisted photo-heating allows for temperature increases of up to several hundred Kelvins which lead to thermally-activated moment reversals and a pronounced reduction of the magnetic coercive field. Furthermore the polarization-dependent absorption cross section of elongated plasmonic elements enables sublattice-specific heating on sub-nanosecond time scales which is not possible with conventional heating schemes. The experimentally quantify the optical and magnetic properties of arrays of single hybrid elements as well as vertex-like assemblies and present strategies how to achieve efficient, fast and selective control of the thermally-activated magnetic reversal by choice of focal point, pump power, light polarization and pulse duration. Therefore the development of efficient non-invasive plasmon-assisted optical heating of nanomagnets allows flexible control of length and time scales of the thermal excitation in magnetic metamaterials. This enables deeper studies of equilibrium properties and emergent excitations in artificial spin systems as well as open doors for the practical use in applications such as low-power nanomagnetic computation.