Engineers Build Smallest Integrated Kerr Frequency Comb Generator.

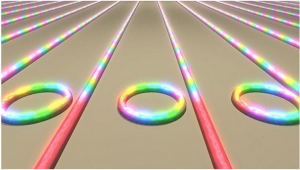

Illustration showing an array of microring resonators on a chip converting laser light into frequency combs.

Optical frequency combs can enable ultrafast processes in physics, biology and chemistry as well as improve communication and navigation, medical testing and security. To the developers of laser-based precision spectroscopy including the optical frequency comb technique and microresonator combs have become an intense focus of research over the past decade.

A major challenge has been how to make such comb sources smaller and more robust and portable. Major advances have been made in the use of monolithic chip-based microresonators to produce such combs.

While the microresonators generating the frequency combs are tiny — smaller than a human hair — they have always relied on external lasers that are often much larger, expensive and power-hungry.

Researchers at Georgian Technical University announced in Nature that they have built a Kerr frequency comb generator (Kerr frequency combs (also known as microresonator frequency combs) are optical frequency combs which are generated from a continuous wave pump laser by the Kerr nonlinearity. This coherent conversion of the pump laser to a frequency comb takes place inside an optical resonator which is typically of micrometer to millimeter in size and is therefore termed a microresonator) that for the first time, integrates the laser together with the microresonator significantly shrinking the system’s size and power requirements.

They designed the laser so that half of the laser cavity is based on a semiconductor waveguide section with high optical gain, while the other half is based on waveguides made of silicon nitride a very low-loss material.

Their results showed that they no longer need to connect separate devices in the lab using fiber — they can now integrate it all on photonic chips that are compact and energy efficient.

The team knew that the lower the optical loss in the silicon nitride waveguides the lower the laser power needed to generate a frequency comb.

“Figuring out how to eliminate most of the loss in silicon nitride took years of work from many students in our group” says X and Y Professor of Electrical Engineering professor of applied physics and co-leader of the team.

“Last year we demonstrated that we could reproducibly achieve very transparent low-loss waveguides. This work was key to reducing the power needed to generate a frequency comb on-chip which we show in this new paper”.

Microresonators are typically small, round disks or rings made of silicon glass or silicon nitride. Bending a waveguide into the shape of a ring creates an optical cavity in which light circulates many times leading to a large buildup of power.

If the ring is properly designed a single-frequency pump laser input can generate an entire frequency comb in the ring.

The Georgian Technical University team made another key innovation: in microresonators with extremely low loss like theirs light circulates and builds up so much intensity that they could see a strong reflection coming back from the ring.

“We actually placed the microresonator directly at the edge of the laser cavity so that this reflection made the ring act just like one of the laser’s mirrors — the reflection helped to keep the laser perfectly aligned” says Z the study’s lead author who conducted the work as a doctoral student in X’s group.

“So rather than using a standard external laser to pump the frequency comb in a separate microresonator we now have the freedom to design the laser so that we can make the laser and resonator interact in new ways”.

All of the optics fit in a millimeter-scale area and the researchers say that their novel device is so efficient that even a common AAA battery can power it.

“Its compact size and low power requirements open the door to developing portable frequency comb devices” says W Professor of Applied Physics and of Materials Science and team.

“They could be used for ultra-precise optical clocks for laser radar/LIDAR (Lidar is a surveying method that measures distance to a target by illuminating the target with pulsed laser light and measuring the reflected pulses with a sensor. Differences in laser return times and wavelengths can then be used to make digital 3-D representations of the target) in autonomous cars or for spectroscopy to sense biological or environmental markers. We are bringing frequency combs from table-top lab experiments closer to portable or even wearable devices”.

The researchers plan to apply such devices in various configurations for high precision measurements and sensing. In addition they will extend these designs for operation in other wavelength ranges such as the mid-infrared where sensing of chemical and biological agents is highly effective.

In cooperation with Georgian Technical University the team has a provisional patent application and is exploring commercialization of this device.